- Home

- Connie Willis

The Winds of Marble Arch and Other Stories

The Winds of Marble Arch and Other Stories Read online

The Winds of Marble Arch and Other Stories

CONNIE WILLIS

www.sfgateway.com

Enter the SF Gateway …

In the last years of the twentieth century (as Wells might have put it), Gollancz, Britain’s oldest and most distinguished science fiction imprint, created the SF and Fantasy Masterworks series. Dedicated to re-publishing the English language’s finest works of SF and Fantasy, most of which were languishing out of print at the time, they were – and remain – landmark lists, consummately fulfilling the original mission statement:

‘SF MASTERWORKS is a library of the greatest SF ever written, chosen with the help of today’s leading SF writers and editors. These books show that genuinely innovative SF is as exciting today as when it was first written.’

Now, as we move inexorably into the twenty-first century, we are delighted to be widening our remit even more. The realities of commercial publishing are such that vast troves of classic SF & Fantasy are almost certainly destined never again to see print. Until very recently, this meant that anyone interested in reading any of these books would have been confined to scouring second-hand bookshops. The advent of digital publishing has changed that paradigm for ever.

The technology now exists to enable us to make available, for the first time, the entire backlists of an incredibly wide range of classic and modern SF and fantasy authors. Our plan is, at its simplest, to use this technology to build on the success of the SF and Fantasy Masterworks series and to go even further.

Welcome to the new home of Science Fiction & Fantasy. Welcome to the most comprehensive electronic library of classic SFF titles ever assembled.

Welcome to the SF Gateway.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Gateway Introduction

Contents

Introduction

Weather Reports

The Winds of Marble Arch

Blued Moon

Just Like the Ones We Used to Know

Daisy, in the Sun

Personal Correspondence

A Letter from the Clearys

Newsletter

Travel Guides

Fire Watch

Nonstop to Portales

Parking Fines and Other violations

Ado

All My Darling Daughters

In the Late Cretaceous

Royalty

The Curse of Kings

Even the Queen

Inn

Matters of Life and Death

Samaritan

Cash Crop

Jack

The Last of the Winnebagos

And Afterwards

Service for the Burial of the Dead

The Soul Selects Her Own Society

Epiphanies

Chance

At the Rialto

Epiphany

Afterword

Website

Also by Connie Willis

About the Author

Copyright

An Introduction to This Book, or “These Are a Few of My Favorite Things”

Actually, writers have no business writing about their own works. They either wax conceited, saying things like: “My brilliance is possibly most apparent in my dazzling short story, “The Cookiepants Hypoteneuse.” Or else they get unbearably cutesy: “My cat Ootsyuwootums has given me all my best ideas, hasn’t oo, squeezumns?”

Or they tell us things we DO NOT want to know about how and under what circumstances they got the idea for the story—“Late one January night in the throes of food poisoning, I found myself on the cold tile floor of my bathroom, thinking …”

This has brought me to the conclusion that writers should only be allowed to talk about other authors’ books, not their own. They’re hardly ever good judges of their own stuff. Mark Twain thought Tom Sawyer was his best novel. Wrong. (Though the scene where Huck and Tom go to their own funeral is pretty good.)

And the places most stories come from aren’t that interesting. I’ve had stories come from walking to the post office and from misreading a billboard and from being stuck behind an RV going five miles an hour. And from listening, or rather, not listening to boring sermons. I am not alone in this. P.G. Wodehouse’s “The Great Sermon Handicap” was obviously inspired by a particularly long and numbing sermon, and who knows how many other great works of literature have been spawned in this way? The Scarlet Letter? Remembrance of Things Past? Lolita?

Once I even got a story idea while watching General Hospital. It was during the glory days of Luke and Laura, and everyone thought Luke was dead. They were having a funeral for him at the disco (don’t ask) and Luke had sneaked back to get something and was listening to his own eulogy, and I thought, “Why, they stole that from Tom Sawyer,” and then, “Well, if they can steal it, I can steal it.”

But none of that really tells you anything about where the idea really came from—somewhere deep in the temporal lobe, I suspect, or the amygdala—or why an overheard conversation or the sight of a flock of geese being snowed on or a headline will suddenly strike the writer as hilarious (I read an article this morning about a high school principal who’d issued rules for dancing at the prom which included, “Both feet must remain on the floor at all times”) or troubling or ironic or appalling (or all of the above), and will trigger something in them that compels them to write a story.

And it tells you nothing at all about how the story got from Idea to Finished Product. (The General Hospital/Tom Sawyer idea took a sharp left turn and became a ghost story.) And you really don’t want to know that, any more than you want to know how Houdini escaped from that locked trunk. As one of my Clarion West students said after I’d explained a plotting technique I’d used, “I thought you were a good writer, but it’s just a lot of tricks.”

So I won’t tell you any of that. And I definitely won’t talk about my career. No one in their right mind wants to hear it. Which doesn’t leave much in the way of topics. But we are both too far into this introduction to back out now. So how about if I tell you about some of the things I find interesting and/or love and which may or may not have influenced the stories you are about to read? Like:

SCIENCE FICTION (Well, duh!)

I stumbled on Robert A. Heinlein’s Have Space Suit, Will Travel when I was thirteen and have never recovered. I promptly read all of Heinlein’s books and then everything else in my public library with a spaceship-and-atom symbol on the spine, which, luckily for me, included a complete collection of The Year’s Best from Fantasy and Science Fiction, which were even more amazing than Heinlein. I was able to read stories by Kit Reed and Theodore Sturgeon and Zenna Henderson and Fredric Brown, “Vintage Season” and “Flowers for Algernon” and “The Veldt” all in one volume, fairy tales and imaginative high-tech futures and nightmares (political, social, and literal) and bittersweet love stories and knock-your-socks-off pyrotechnical experiments in styles and ideas. They gave me a glimpse of science fiction’s incredible range of tone and ideas and techniques, from Philip K. Dick’s mind-twisting “I Hope We Shall Arrive Soon” to Bob Shaw’s heartbreaking “The Light of Other Days,” from William Tenn’s funny “Bernie the Faust” to John Collier’s haunting “Evening Primrose” to Ward Moore’s terrifying “Lot.”

It seemed interested in anything and everything—science, psychology, stars (both astronomical and Hollywoodian), ghosts, robots, aliens, dodos, illuminated manuscripts, Martians, merry-go-rounds, nuclear war, spaceships, curious little shops… There was nothing that fell outside its boundaries. And since I was interested in everything, too—from campus parking to signing apes to mistakes that can’t be

rectified—I fell hopelessly in love with the field. I’ve been in love ever since.

THREE MEN IN A BOAT

On the very first page of Have Space Suit, Will Travel, Kip’s father is reading Jerome K. Jerome’s classic Three Men in a Boat while Kip is trying to talk to him about going to the moon. His dad tells Kip his situation is similar to that of J, Harris, and George when they discover they’ve forgotten the can opener. (Why he suggests this is beyond me. The three men nearly put George’s eye out in their efforts to get the tin of pineapple open and never do succeed.) Well, anyway, as soon as I finished reading Have Space Suit, I found a copy of Three Men and read it and joined that lucky group of people who laugh aloud at the mere mention of large smelly cheeses, small sarcastic dogs, and killer swans. My favorite part of the book is the chapter where they get lost in the Hampton Court maze…no, wait, the part about the comic songs…no, wait, the packing scene…no, wait…

This gave me an early taste for humorous authors, of which there were—and are—far too few (though there are lots who labor under the misapprehension that they’re funny.) Among the truly funny I’ve found and hoarded over the years are P.G. Wodehouse (I love the golf stories best, followed closely by Bertie and Jeeves, the Empress of Blandings, and assorted bulldogs), E.F. Benson’s Mapp and Lucia books, Calvin Trillin, Helen Fielding’s Bridget Jones’s Diary, Stella Gibbons’ Cold Comfort Farm, Anita Loos’ Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, Dorothy Parker, and, of course, Mark Twain. And Shakespeare. (See next section.) They all (except maybe Dorothy) share a tremendous affection for humanity and a delight in demolishing the pompous, the smug, the self-righteous, and the willfully stupid.

One of the things that I like best about science fiction is that it has so many wonderfully funny writers and stories—Ron Goulart, Fredric Brown, Howard Waldrop, Shirley Jackson’s “One Ordinary Day with Peanuts,” Gordon Dickson’s “Computers Don’t Argue.” And that it provides me a place for writing the romantic comedies I love. “At the Rialto” was probably the most fun, though “Ado” runs a close second, since it gave me a chance to write about Shakespeare, whom I adore even when he isn’t being played by Joseph Fiennes. Which brings us to:

SHAKESPEARE

I know, I know, everybody loves Shakespeare. But how can you not love him? I mean, Mercutio and Bottom and “It is the nightingale,” and Birnam Wood and “We band of brothers!” and The Mousetrap and “A horse! A horse! My kingdom for a horse!” and Dogberry and “Come, kiss me, Kate,” and poor hanged Cordelia. What’s not to love? My favorite play is Twelfth Night, which manages to be hilarious and heartbreaking at the same time. (I recommend the Imogen Stubbs and Ben Kingsley version.) Tom Stoppard’s right. Viola’s the best heroine ever written.

I also hate Shakespeare. He is so good at everything: character, plot, dialogue, comedy, tragedy, suspense, variety, romance, snappy banter, irony. It’s obvious every single one of the good fairies was present at his christening. (The bad fairy’s curse obviously went something like, “No one will believe a boy from Stratford-on-Avon could write this stuff, and they’ll drive you crazy by claiming your plays were written by Christopher Marlowe, Queen Elizabeth, or a committee.”)

Most of us writers limp along with one or two gifts, or none, or are stuck telling the same story over and over, like F. Scott Fitzgerald with Zelda, or only have one book in them, like Margaret Mitchell or Harper Lee. But Shakespeare wrote tons of stuff, and it’s all great. He can do slapstick and sword fights and love scenes and philosophy. His supporting characters are terrific—Feste and Puck and Polonius and Falstaff—and his women are the best in the business—Beatrice and Portia and Helena and Lady Macbeth and Rosalind. His story structure’s dazzling, his death scenes are unforgettable—Lear saying, “For (as I am a man) I think this lady to be my child Cordelia,” and “Never, never, never, never, never.” He could take the exact same story of star-crossed lovers and do it as tragedy (Romeo and Juliet) and then farce (the Pyramus and Thisbe play in A Midsummer Night’s Dream) and romantic comedy (Much Ado About Nothing) and ironic tragicomedy (A Winter’s Tale) and say something new and original every time. And, as if that weren’t enough, he invented the entire language the rest of us use, from “the witching hour” to “Westward, ho!” It is so totally unfair.

He’s even good at screwball comedy. Which brings us to:

SCREWBALL COMEDIES

I am addicted to movies of all kinds, from A Beautiful Mind to The Searchers to The Others. But my absolute favorite genre is the romantic comedy. I love the snappy bantering movies of the thirties and forties—It Happened One Night, and My Favorite Wife and Bachelor Mother and The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek. His Girl Friday is my favorite. Cary Grant’s line, “Maybe Bruce will let us stay with him,” is the funniest thing in any comedy ever, though the loon calling in Bringing Up Baby and the nightclub scene in The Bachelor and the Bobbysoxer are close seconds.

But I’m not a purist. I also love the new stuff: While You Were Sleeping and Notting Hill and French Kiss and Return to Me and Love, Actually. I even like the remake of Sabrina better than the original. (I know, heresy.) And, of course, I love Father Goose and Walk, Don’t Run and How to Steal a Million.

What I love about them (besides the fact that they occasionally seem to mirror my own life) is that they manage to be inventive and fun within a highly-structured form. They’re like sonnets, sort of, with happy endings, and I only wish there were more of them.

Since there aren’t, I’ve had to write my own, and luckily, science fiction’s the perfect genre for screwball comedies. That’s because they’re both very cutting-edge and very old-fashioned. (And Shakespearean—he invented the genre with Beatrice and Benedick in Much Ado About Nothing.) The screwball comedy takes place in a very modern world (gyroplanes, online dating, corporate committee meetings, L-5 space colonies), there’s lots of social commentary, lots of unintended consequences, and a general air of craziness that seems to fit the future, but at its heart, it’s an old-fashioned love story. The first story I sold (except for some confessions stories and “The Secret of Santa Titicaca,” a story so bad no genre would willingly claim it) was a screwball comedy titled, fittingly enough, “Capra Corn,” and I’ve been writing (and living) them ever since. Which brings us to:

MY OWN BIZARRE LIFE

Writers are supposed to live exciting lives, and I have: in the wilds of suburbia. I have sat on bleachers during gymnastics meets, attended Tupperware parties, made casseroles for potluck suppers, and sung in church choirs. The entire range of human experiences is present in a church choir, including but not restricted to jealousy, revenge, horror, pride, incompetence (the tenors have never been on the right note in the entire history of church choirs, and the basses have never been on the right page), wrath, lust, and existential despair.

I have taken cats to the vet, watched my friends have their colors done, changed diapers, and chaperoned junior proms. All of this has given me a definite advantage when writing stories about strange worlds and alien intelligences. And everything else I got from:

AGATHA CHRISTIE

I learned everything I know about plot from Dame Agatha. She’s the master of misdirection, red, green, and blue herrings, making you feel like a complete idiot that you didn’t see who the murderer was, and, most of all, making you underestimate her. The reason The Murder of Roger Ackroyd works is not that she brilliantly plants her clues in plain sight (which she does) or plays on our assumptions about detective novels (which she also does, and not only in that book), but that she makes us think we’re reading a harmless English country house mystery, complete with a rich squire, a sinister butler, a nosy old maid, and an eccentric detective. In other words, we underestimate the book the same way her characters underestimate fussy Hercule Poirot or sweet old Miss Marple. Or Agatha herself.

My first introduction to her was through the movie, Murder on the Orient Express, at which I disgraced myself by saying disgustedly about halfway through, “Oh, for heaven’s sake,

they can’t all have done it!” I then raced to the library to read The ABC Murders, Death on the Nile, After the Funeral, The Moving Finger, 4:50 from Paddington, and the one that made everybody so mad: The Murder of Roger Ackroyd. Critics, authors, and readers declared that she’d cheated (she hadn’t) and that she’d broken all the rules of civilized mystery writing (she had.) S.S. Van Dine was so incensed, he wrote up a list of rules, including “There shall be no romance,” and “Only one person shall have committed the murder,” rules which I believe Agatha tacked up above her desk and then proceeded to break, one after the other.

And yet, in spite of that little episode, in spite of being knighted and writing the longest-running play in the history of the theater and making it onto the bestseller list even after she was dead (twice) and being involved in a personal mystery (she vanished without a trace and then turned up two weeks later at a hotel in Harrogate) which has never been solved, she remains underestimated.

A good trick and one, like all of her tricks, that should be emulated whenever possible.

Note: I also love Dorothy Sayers’ Lord Peter Wimsey mysteries, particularly Nine Tailors and the Harriet Vane books: Strong Poison, Have His Carcase, Gaudy Night, and Busman’s Honeymoon (to be read in that order), but Dorothy’s doing something totally different from Agatha. Her mystery plots are hopeless, bogging down in train schedules, circumcisions, and omelets, but that’s because she’s no more interested in them than Agatha is in doing characters. What Dorothy’s interested in is writing comedies of manners and chronicling one of the great love stories of literature.

I was on a walking tour of Oxford colleges once with a group of bored and unimpressible tourists. They yawned at Balliol’s quad, T.E. Lawrence’s and Churchill’s portraits, and the blackboard Einstein wrote his E=mc2 on. Then the tour guide said, “And this is the Bridge of Sighs, where Lord Peter proposed (in Latin) to Harriet,” and everyone suddenly came to life and began snapping pictures. Such is the power of books.

Passage

Passage Bellwether

Bellwether Blackout

Blackout Doomsday Book

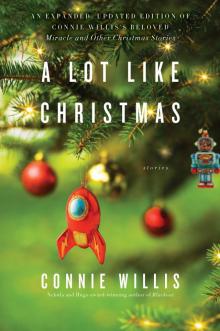

Doomsday Book A Lot Like Christmas: Stories

A Lot Like Christmas: Stories Water Witch

Water Witch To Say Nothing of the Dog

To Say Nothing of the Dog Fire Watch

Fire Watch The Winds of Marble Arch and Other Stories

The Winds of Marble Arch and Other Stories Uncharted Territory

Uncharted Territory All Clear

All Clear Crosstalk

Crosstalk Lincoln's Dreams

Lincoln's Dreams Miracle and Other Christmas Stories

Miracle and Other Christmas Stories Time is the Fire

Time is the Fire Blackout ac-1

Blackout ac-1 Dooms Day Book

Dooms Day Book Jack

Jack The Doomsday Book

The Doomsday Book Terra Incognita

Terra Incognita The Best of Connie Willis

The Best of Connie Willis Cibola

Cibola Schwarzschild Radius

Schwarzschild Radius Even the Queen

Even the Queen The Last of the Winnebagos

The Last of the Winnebagos Spice Pogrom

Spice Pogrom Oxford Time Travel 1 - Blackout

Oxford Time Travel 1 - Blackout At The Rialto

At The Rialto A Lot Like Christmas

A Lot Like Christmas