- Home

- Connie Willis

The Winds of Marble Arch and Other Stories Page 2

The Winds of Marble Arch and Other Stories Read online

Page 2

Finally, my biggest and most important influence has been:

THE PUBLIC LIBRARY

I was born into a family that didn’t read and that didn’t own many books. My mother had a movie edition of Gone with the Wind, my grandmother subscribed to Redbook and The Saturday Evening Post, and the girl across the street had a copy of A Little Princess, and that was about it. Consequently, pretty much everything I read came from the public library, and I spent as much time there as I could.

It was there that I discovered science fiction and Anne of Green Gables and Lenora Mattingly Weber and H.V. Morton’s London, which was where I first read about the St. Paul’s fire watch in World War II sleeping in the crypts of the cathedral during the day and putting out incendiaries on the roofs at night. I wrote Doomsday Book in the public library, and “Chance” and “A Letter from the Clearys,” and I researched Passage and “Fire Watch” and “Just Like the Ones We Used to Know” there. The public library was where I read about the Hindenburg and Emily Dickinson and the curse of Tutankhamen.

When I was eleven, I decided to read my way through the library alphabetically just like Francie in A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, and, in doing so, found James Agee’s A Death in the Family and Jane Austen and Peter Beagle’s A Fine and Private Place before stumbling onto science fiction. And it was in the library that I found all sorts of things I wasn’t looking for at all—books on chaos theory and literary criticism, an article on body sniffers in the Blitz and one about Aberfan in Wales, where all the children had been killed when the coal tip slid down on the school, and scientific articles about the EPR paradox and the effect of large particulates on the color of the stratosphere.

I couldn’t have become a writer—or anything—without the public library, and it appears in some guise or other in every one of my stories. And quite a few of those stories are in this book. I hope you enjoy them.

Connie Willis

March 3, 2007

Weather Reports

The Winds of Marble Arch

Cath refused to take the tube.

“You loved it the last time we were here,” I said, rummaging through my suitcase for a tie.

“Correction. You loved it,” she said, brushing her short hair. “I thought it was dirty and smelly and dangerous.”

“You’re thinking of the New York subway. This is the London Underground.” The tie wasn’t there. I unzipped the side pocket and jammed my hand down it. “You rode the tube the last time we were here.”

“I also carried my suitcase up five flights of stairs at that awful bed and breakfast we stayed at. I have no intention of doing that either.” She wouldn’t have to. The Connaught had a lift and a bellman.

“I hated the tube,” she said. “I only took it because we couldn’t afford taxis. And now we can.”

We certainly could. We could also afford a hotel with carpet on the floor and a bathroom in our room instead of down the hall. A far cry from the—what was it called? It had had brown linoleum floors you hadn’t wanted to walk on in your bare feet, and you had to put coins in a meter above the bathtub to get hot water.

“What was the name of that place we stayed at?” I asked Cath.

“I’ve repressed it,” she said. “All I remember is that the tube station had the name of a cemetery.”

“Marble Arch,” I said, “and it wasn’t named after a cemetery. It was named after the copy of the Roman arch of Constantine in Hyde Park.”

“Well, it sounded like a cemetery.”

“The Royal Hernia!” I said, suddenly remembering.

Cath grinned. “The Royal Heritage.”

“The Royal Hernia of Marble Arch,” I said. “We should go visit it, just for old times’ sake.”

“I doubt if it’s still there,” she said, putting on her earrings. “It’s been twenty years.”

“Of course it’s still there,” I said. “Scummy showers and all. Do you remember those narrow beds? They were just like coffins, only at least coffins have sides so you don’t roll off.” The tie wasn’t there. I started taking shirts out of the suitcase and piling them on the bed. “These aren’t much better. It makes you wonder how the British have managed to reproduce all these years.”

“We seemed to manage all right,” Cath said, putting on her shoes. “What time does the conference start?”

“Ten,” I said, dumping socks and underwear onto the bed. “What time are you meeting Sara?”

“Nine-thirty,” she said, looking at her watch. “Will you have time to pick up the tickets for the play?”

“Sure,” I said. “The Old Man won’t show up before eleven.”

“Good,” she said. “Sara and Elliott can only go Saturday. They’ve got something tomorrow night, and we’ve got dinner with Milford Hughes’s widow and her sons Friday night. Is Arthur going with us to the play? Did you get in touch with him?”

“No, but I know the Old Man’ll want to go. What are we seeing?” I asked, giving up on the tie.

“Ragtime, if we can get tickets. It’s at the Adelphi. If not, try to get The Tempest or Sunset Boulevard, and if they’re sold out, Endgames. Hayley Mills is in it.”

“Kismet isn’t playing?”

She grinned again. “Kismet isn’t playing.”

“Which tube stop does it say for the Adelphi?”

“Charing Cross,” she said, consulting the map. “Sunset Boulevard’s at the Old Vic, and The Tempest’s at the Duke of York. On Shaftesbury Avenue. You could get the tickets through a ticket agent. It would be a lot faster than going to the theaters.”

“Not on the tube, it won’t,” I said. “It’s a snap to go anywhere. And ticket agents are for tourists.”

She looked skeptical. “Get third row if you can, but not on the sides. And no farther back than the dress circle.”

“Not the balcony?” I asked. The farthest, highest seats had been all we could afford the first time we were here, so high up all you could see was the tops of the actors’ heads. When we’d gone to Kismet, the Old Man had spent the entire time leaning forward to look down the well-endowed Lalume’s Arabian costume through a pair of rental binoculars.

“Not the balcony,” Cath said, sticking an umbrella and the guidebook in her bag. “Put it on the American Express, if they’ll take it. If not, the Visa.”

“Are you sure the third row’s a good idea?” I said. “Remember, the Old Man nearly got us thrown out of the upper balcony the last time, and there wasn’t even anybody else up there.”

Cath stopped putting things in her bag. “Tom,” she said, looking worried. “It’s been twenty years, and you haven’t seen Arthur in over five.”

“And you think the Old Man will have grown up in the meantime?” I said. “Not a chance. This is the guy who got us thrown out of Graceland five years ago. He’ll still be the same.”

Cath looked like she was going to say something else, and then began putting stuff in her bag again. “What time is the cocktail party tonight?”

“Sherry party,” I said. “They have sherry parties here. Six. I’ll meet you back here, okay? Or is that enough time for you and Sara to buy out the town and catch up on—what is it?—three years’ gossip?”

I’d seen Elliott and Sara last year in Atlanta and the year before that in Barcelona, but Cath hadn’t come with me to either conference. “Where are you doing all this shopping?” I asked.

“Harrods,” she said. “Remember the tea set I bought the first time we were here? I’m going to buy the matching china. And a scarf at Liberty’s and a cashmere cardigan, all the things we couldn’t afford last time.” She looked at her watch again. “And I’d better get going. The traffic’s going to be bad in this rain.”

“The tube would be faster,” I said. “And drier. You take the Piccadilly line to Knightsbridge, and you’re right there. You don’t even have to go outside. There’s an entrance to Harrods right in the tube station.”

“I am not maneuvering shopping bags up and down those aw

ful escalators,” she said. “They’re broken half the time. Besides, there are rats.”

“You saw one mouse in Piccadilly Circus one time, and it was down on the tracks,” I said.

“It’s been twenty years,” she said, coming over to the bed and deftly pulling my tie out of the mess. “There are probably thousands of rats down there now.” She kissed me on the cheek. “Good luck presenting your paper.” She grabbed up an umbrella. “You take the tube,” she said, going out the door. “You’re the one who’s crazy about it.

“I intend to,” I called after her, but the lift had already closed.

In spite of Cath’s dire predictions, the tube was exactly the same as it had been twenty years ago. Well, maybe not exactly. There were ticket machines now, and automated stiles that sucked up my five-day pass and spit it out to me again. And the escalators were metal now instead of wooden. But they were as steep as ever, and the posters for musicals and plays that lined them had hardly changed at all. Kismet and Cats had been playing then. Now it was Showboat and Cats.

Cath was right—I did love the tube. It’s the best underground system in the world. Boston’s T is old and decrepit, Tokyo’s subway system is a sardine can, and Washington’s Metro looks like it was designed as a bomb shelter. The Metro’s not bad, but it has the handicap of being in Paris. BART’s in San Francisco, but it doesn’t go anywhere.

The tube goes everywhere, all the way to Heathrow and Hampton Court and beyond, to obscure suburban stops like Cockfosters and Mudchute. There’s a stop at every tourist attraction, and it’s impossible to get lost.

But it isn’t just an efficient way of getting from the Tower to Westminster Abbey to Buckingham Palace. It’s a place in itself, a wonderful underground warren of tunnels and stairs and corridors, as colorful as the billboard-sized theater posters on the walls of the platforms, as the maps posted on every pillar and wall and forking of the tunnels.

I stopped in front of one, studying the crisscrossing green and blue and red lines. Charing Cross. I needed the gray line. What was that? Jubilee.

I followed the signs down a curving platform and out onto the eastbound platform.

A train was pulling out. An LED sign above the tracks said NEXT TRAIN 6 MIN. The train started into the narrow tunnel, and I waited for the blast of wind that would follow it, pushing the air in front of it as the train disappeared.

It came, smelling faintly of diesel and dust, ruffling the hair of the woman standing next to me, rippling her skirt. NEXT TRAIN 5 MIN., the sign said.

I filled the time by watching a pair of newlyweds holding hands and reading the posters on the tunnel walls for Sunset Boulevard and Sliding Doors and Harrods. “A Blast from the Past,” the one on the end said. “Experience the London Blitz at the Imperial War Museum. Elephant and Castle Tube Station.”

“Train approaching,” a voice said from nowhere, and I stepped forward to the yellow line.

The familiar MIND THE GAP sign was still painted on the edge of the platform. Cath had always refused to stand anywhere near the edge. She had stood nervously against the tiled wall as if she expected the train to suddenly leap off the tracks and plow into us.

The train pulled in. Right on time, shining chrome and plastic, no gum on the floor, no unknown substances on the orange plush seats.

“I beg your pardon,” the woman next to me said, shifting her shopping bag so I could sit down.

Even the people who rode the tube were more polite than people on any other subway. And better read. The man opposite me was reading Dickens’ Bleak House.

The train slowed. “Regent’s Park,” the flat voice announced.

Regent’s Park. The last time we were here, the Old Man had shouted “To the head!” and vaulted off the train at this station.

He had been taking us on a riotous tour of Sir Thomas More’s body. We had gone to the Tower of London to see the Crown Jewels, and Cath, reading her Frommer’s England on $40 a Day while we stood in line, had said, “Sir Thomas More is buried in the church here. You know, A Man for All Seasons,” and we had all trooped over to see his grave.

“Want to see the rest of him?” the Old Man had said.

“The rest of him?” Sara had asked.

“Only his body’s buried there,” the Old Man had said. “You need to see his head!” and had led us off to London Bridge, where More’s head had been stuck on a pike, and the Chelsea garden where his daughter Margaret had buried it after she took it down, and then off to Canterbury, with the Old Man turned around and talking to us as he drove, to the small church where the head was buried now.

“Thomas More’s Remains: The World Tour,” he had said, driving us back at breakneck speed.

“Except for Lake Havasu,” Elliott had said. “Isn’t that where the original London Bridge is?” And when the annual conference was in San Diego, the Old Man had roared up in a rental car and hijacked us all to Arizona to see it.

I couldn’t wait to see him. There was no telling what wild sightseeing he had in mind this time. This was, after all, the man who had gotten us thrown out of Alcatraz.

He hadn’t been at the last four conferences—he’d been off in Nepal for the first one and finishing a book the last three—and I was eager to hear what he’d been up to.

“Oxford Circus,” the flat voice said. Two more stops to Charing Cross.

I leaned out to look at the station as we stopped. Each station has its own distinctive design, its own identifying color: St. Pancras green edged with navy, Euston Square black and orange, Bond Street red. Oxford Circus had a blue chutes and ladders design that was new since the first time we’d been here.

The train pulled out, picked up speed. I would be there in five minutes and to the Adelphi in ten, a lot faster than Cath in her taxi, and at least as comfortable.

I was there in eight, up the escalators and out in the rain, up the Strand to the Adelphi in twenty. It would have been fifteen, but I had to wait ten (huddled under an awning and wishing I’d taken Cath’s advice about an umbrella) to cross the Strand. Black London taxis, bumper to bumper, and double-decker buses, and minis, all going nowhere fast.

Ragtime was sold out. I got a theater map from the rack in the lobby and looked to see where the Duke of York was. It was over on Shaftesbury, with the nearest tube stop Leicester Square. I went back to Charing Cross, and went down the escalator and into the passage that led to the Northern Line. I still had half an hour, which would be cutting it close, but not impossible.

I started down the left-hand tunnel toward the trains, keeping pace with the crowd, straining to hear the rumble of a train pulling in over the muffled din of voices, the crisp clatter of high heels.

People began to walk faster. The high heels beat a quicker tattoo. I got the tube map out of my back pocket. I could take the Piccadilly Line to South Kensington and change to the District and—

The wind hit me like the blast from an explosion. I reeled back, nearly losing my balance. My head snapped back sharply like I’d been punched in the jaw. I groped wildly for the tiled wall.

“The IRA’s blown up a train!” I thought.

But there was no sound accompanying the sudden blast of searing air, only a dank, horrible smell.

Sarin gas, I thought, and reflexively put my hand over my nose and mouth, but I could still smell it. Sulfur and a wet earthy smell, and something else. Gunpowder? Dynamite? I sniffed at the air, trying to identify it.

But whatever it was, it was already over. The wind had stopped as abruptly as it had hit me, and so had the smell. Not even a trace of it lingered in the dry, stuffy air.

And it must not have been an explosion, or poison gas, because no one else had even slackened their steps. The sound of high heels retained its brisk, even clatter down the tiled passage. Two German teenagers with backpacks hurried past, giggling, and a businessman in a gray topcoat, the Times tucked under his arm, and a young woman in floppy sandals, all of them oblivious.

Hadn’t any of the

m felt it? Or was it a usual occurrence in Charing Cross Station and they were used to it?

How could anybody possibly get used to a blast like that? They must not have felt it.

Had I felt it?

It was like an earthquake back home in California, a jolt, and then before you could even register it, it was over, and you weren’t sure it had really happened. The only way you could tell for sure was by asking Cath or the kids, “Did you feel that?” or by the picture tilted on the wall.

The only pictures on the walls down here were pasted on, and the German students, the businessman had already told me the answer to “Did you feel that?”

But I felt it, I thought, and tried to reconstruct it. Heat, and the sharp tang of sulfur and wet dirt. But that wasn’t what had made me lose my balance, what had sent me staggering against the wall. It was the smell of panic and people screaming, of a bomb going off.

But it couldn’t be a bomb. The IRA was in peace negotiations with the British, there hadn’t been an incident for over a year, and bombs didn’t stop in mid-blast. There had been bombs in the tube before—the mechanical voice would be saying, “Please exit up the escalator immediately,” not, “Mind the gap.”

But if it wasn’t a bomb, what was it? And where had it come from? I looked up at the roof of the passage, but there wasn’t a grate or a vent, no water pipes running along the ceiling. I walked along the tunnel, sniffing the air, but there were only the usual smells—dust and damp wool and cigarette smoke, and, where the passage went up a short flight of stairs, a strong smell of oil.

A train rumbled in somewhere down the passage. The train. There had been one pulling in when it hit. It must be causing the wind somehow. I went out onto the platform and stood there looking down the tunnel, half-hoping, half-dreading it would happen again.

Passage

Passage Bellwether

Bellwether Blackout

Blackout Doomsday Book

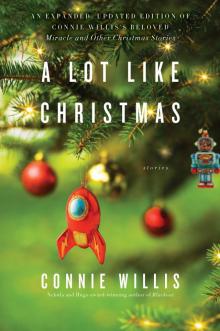

Doomsday Book A Lot Like Christmas: Stories

A Lot Like Christmas: Stories Water Witch

Water Witch To Say Nothing of the Dog

To Say Nothing of the Dog Fire Watch

Fire Watch The Winds of Marble Arch and Other Stories

The Winds of Marble Arch and Other Stories Uncharted Territory

Uncharted Territory All Clear

All Clear Crosstalk

Crosstalk Lincoln's Dreams

Lincoln's Dreams Miracle and Other Christmas Stories

Miracle and Other Christmas Stories Time is the Fire

Time is the Fire Blackout ac-1

Blackout ac-1 Dooms Day Book

Dooms Day Book Jack

Jack The Doomsday Book

The Doomsday Book Terra Incognita

Terra Incognita The Best of Connie Willis

The Best of Connie Willis Cibola

Cibola Schwarzschild Radius

Schwarzschild Radius Even the Queen

Even the Queen The Last of the Winnebagos

The Last of the Winnebagos Spice Pogrom

Spice Pogrom Oxford Time Travel 1 - Blackout

Oxford Time Travel 1 - Blackout At The Rialto

At The Rialto A Lot Like Christmas

A Lot Like Christmas