- Home

- Connie Willis

To Say Nothing of the Dog Page 9

To Say Nothing of the Dog Read online

Page 9

“Balliol,” I said, and then hoped against hope he went to Brasenose or Keble.

“I knew it,” he said happily. “One can always spot a Balliol man. It’s Jowett’s influence. Who’s your tutor?”

Who had been at Balliol in 1888? Jowett, but he wouldn’t have had any pupils. Ruskin? No, he was Christ Church. Ellis? “I was ill this year,” I said, deciding on caution. “I’m coming up again in the autumn.”

“And in the meantime, your physician’s recommended a trip on the river to recover. Fresh air, exercise, and quiet and all that bosh. And rest that knits the ravelled sleeve of care.”

“Yes, exactly,” I said, wondering how he knew that. Perhaps he was my contact after all. “My physician sent me down this morning,” I said, in case he was and was waiting for some sign from me. “From Coventry.”

“Coventry?” he said. “That’s where St. Thomas à Becket’s buried, isn’t it? ‘Who will rid me of this turbulent priest?’”

“No,” I said. “That’s Canterbury.”

“Then which one’s Coventry?” He brightened. “Lady Godiva,” he said. “And Peeping Tom.”

Well, so he wasn’t my contact. Still, it was nice being in a time when those were the associations for Coventry and not ravaged cathedrals and Lady Schrapnell.

“Here’s the thing,” Terence said, sitting down next to me on the bench. “Cyril and I were planning to go on the river this morning, had the boat hired and noinbob put down to hold it and our things all packed, when Professor asks me if I can meet his aged relatives because he’s got to go write about the battle of Salamis. Well, one doesn’t say no to one’s tutor, even if one is in a devil of a hurry, especially when he was such a brick about the whole Martyr’s Memorial thing, not telling my father and all, so I left Cyril down at Folly Bridge to watch our things and make certain Jabez didn’t rent the boat out from under us which he’s done on more than one occasion, including that time Rush-forth’s sister was up for Eights, even with a deposit, and legged it up St. Aldate’s. I could see I was going to be late, so when I got to Pembroke, I hailed a hansom. I only had enough for the balance of the boat, but I was counting on the agèd relicts anteing up. Only he’d got the trains mixed and I can’t draw against my next quarter allowance because I put it all on Beefsteak in the Derby, and Jabez for some reason refuses to extend credit to undergraduates. So here I am, stuck like Mariana in the South, and there’s Cyril, ‘like patience on a monument, smiling at grief.’” He looked at me expectantly.

And, oddly enough, though this was far worse than the jumble sales and I’d only understood about one word in three and none of the literary allusions, I’d got the gist of what he was saying: he didn’t have enough money for the boat.

And of what it meant: he definitely wasn’t my contact. He was only a penniless undergraduate. Or one of Auntie’s “ruffians” who hung about railway stations engaging people in conversation and trying to borrow money. Or worse.

“Hasn’t Cyril any money?” I asked.

“Lord, no,” he said, stretching out his legs. “He never has a shilling. So I was wondering, since you were planning to go on the river and so were we, if we mightn’t combine resources, like Speke and Burton, only of course the sources of the Thames have already been discovered, and we wouldn’t be going upriver, at any rate. And there won’t be any savage natives or tsetse flies or things. Cyril and I wondered if you’d like to go on the river with us.”

“Three men in a boat,” I murmured, wishing he were my contact.Three Men in a Boat has always been one of my favorite books, especially the chapter where Harris gets lost in Hampton Court Maze.

“Cyril and I are going downriver,” Terence was saying. “We were thinking of taking a leisurely trip down to Muchings End, but we could stop anywhere you’d like. There are some nice ruins at Abingdon. Cyril loves ruins. Or there’s Bisham Abbey, where Anne of Cleves waited out the divorce. Or if you had in mind simply drifting along, enjoying the ‘current that with gentle murmur glides,’ we could simply drift.”

I wasn’t listening. Muchings End, he’d said, and I knew as soon as I heard it, it was the name I’d been trying to remember. “Contact someone,” he’d said, and this was clearly the someone. His references to the river and my physician’s orders, his crooked mustache and identical blazer, couldn’t all be coincidences.

I wondered why he didn’t simply tell me who he was, though. There was no one else on the platform. I looked in the station window, trying to see if the station agent was eavesdropping, but I couldn’t see anything. Or perhaps he was just being cautious in case I wasn’t the right person.

I said, “I’m—” and the station door opened, and a portly middle-aged man wearing a bowler and a handlebar mustache came out. He tipped the bowler, grunted something undistin-guishable, and went over to the notice board.

“I should like very much to go with you to Muchings End,” emphasizing the last two words. “A trip on the river will be a restful change from Coventry.”

I fished in my trouser pocket, trying to remember what Finch had done with the purse full of money. “How much do you need for the hire of the boat?”

“Sicksunthree,” he said. “That’s for a week’s hire. I’ve already put noinbob down.”

The purse was in my blazer pocket. “I’m not certain if I brought enough with me,” I said, tipping the banknote and coins out in my hand.

“There’s enough there to buy the boat,” Terence said. “Or the Koh-i-noor. This your kit?” he said, indicating my stacked luggage.

“Yes,” I said, and reached for the portmanteau, but he’d already grabbed it and one of the twine-tied boxes up in one hand, and the satchel and hamper in the other. I grabbed the other box and the carpetbag and the covered basket up and followed him.

“I told the hansom driver to wait,” he said, starting down the steps, but there was nothing outside the station except a mangy spotted hound, lazily scratching its ear with its hind leg. It paid no attention as Terence passed, and I felt another surge of jubilation that I was years and years from vicious dogs and downed Luftwaffe pilots, in a quieter, slower-paced, more decorous time.

“Uncivilized blighter,” Terence said. “I told him to wait. We’ll have to get a cab on Cornmarket.”

The hound shifted position and began licking its private parts. All right. Not entirely decorous.

And not all that slow. “Come along then,” Terence said. “There’s no time to lose,” and took off up Hythe Bridge Street at a near-gallop.

I followed at as fast a clip as I could manage, considering the luggage and Hythe Bridge Street, which was unpaved and badly rutted. It took all my attention to keep my footing and juggle the luggage.

“Come along then,” Terence said, pausing at the top of the hill. “It’s nearly noon.”

“Coming,” I said, adjusting the covered basket, which was slipping, and struggled up the hill to the top.

When I got there, I stopped, gaping as badly as the new recruit had at the cat. I was in the Cornmarket, at the crossroads of St. Aldate’s and the High, under the mediaeval tower.

I had stood here hundreds of times, waiting for a break in the traffic. But that was in Twenty-First Century Oxford, with its tourist shopping centers and tube stations.

This, this was the real Oxford, “with the sun on her towers,” the Oxford of Newman and Lewis Carroll and Tom Brown. There was the High, curving down to Queen’s and Magdalen,and the Old Bodleian, with its high windows and chained books, and next to it the Radcliffe Camera and the Sheldonian Theatre. And there, down on the corner of the Broad, was Balliol in all its glory. The Balliol of Matthew Arnold and Gerard Manley Hopkins and Asquith. Inside those gates was the great Jowett, with his bushy white hair and his masterful voice, telling a student, “Never explain. Never apologize.”

The clock in Cornmarket’s tower struck half past eleven, and all the bells in Oxford chimed in. St. Mary the Virgin, and Christ Church’s Great Tom, and the silvery

peal of Magdalen, far down the High.

Oxford, and I was here in it. In “the city of lost causes” where lingered “the last echoes of the Middle Ages.”

“‘That sweet city with her dreaming spires,’” I said, and was nearly hit by a horseless carriage.

“Jump!” Terence said, lunging for my arm, and pulled me out of the way. “Those things are an absolute menace,” he said, looking longingly after it. “We’re never going to find a hansom in this mess. We’re better off walking,” and plunged in amongst a host of harried-looking women with aprons and market baskets, murmuring, “Sorry,” to them and tipping his hat with the hamper.

I followed him down Cornmarket, through the bustling crowd and past shops and greengrocers’. I glanced in the window of a hatter’s at the people reflected there, and stopped cold. A woman with a basket full of cabbages crashed into me and then went round me, muttering, but I scarcely noticed.

There hadn’t been any mirrors in the lab, and I had only been half aware of the garments Warder was putting on me. I had had no idea. I looked the very image of a Victorian gentleman off for an outing on the river. My stiff collar, my natty blazer and white flannels. Above all, my boater. There are some things one is born to wear, and I had obviously been fated to wear this hat. It was of light straw with a band of blue ribbon, and it gave me a jaunty, dashing look, which, combined with the mustache, was fairly devastating. No wonder Auntie had been so anxious to hustle Maud off.

On closer inspection, my mustache was a bit lopsided, and my eyes had that glazed, time-lagged look, but those could be remedied shortly, and the overall effect was still extremely pleasing, if I did say so my—

“What are you doing, standing there like a sheep?” Terence said, grabbing my arm. “Come along!” He led me across Carfax and down St. Aldate’s.

Terence kept up a cheerful stream of chatter as he went. “Look out for the tram rails. I tripped over one last week. Worse for the carriages, though, just the right size to catch their wheels, and over they go. Well, over I went, and lucky for me that the only thing coming was a farm wagon and a mule old as Methuselah, or I’d have gone to meet my Maker. Do you believe in luck?”

He crossed the street and took off down St. Aldate’s. And there was The Bulldog with its painted pub signboard of angry proctors chasing an undergraduate, and the golden walls of Christ Church, and Tom Tower. And the walled deanery garden, from which came the sound of children laughing. Alice Liddell and her sisters? My heart caught, trying to remember when Charles Dodgson had written Alice in Wonderland. No, it had been written earlier, in the 1860s. But there, across the street, was the shop where Alice had bought sweets from a sheep.

“The day before yesterday I’d have told you I didn’t believe in luck,” Terence said, trotting past the path to Christ Church Meadow. “But after yesterday afternoon, I’m a true believer. So many things have happened. Professor Peddick getting the trains mixed, and then you being there. I mean, you might have been going somewhere else altogether, or you mightn’t have had the money for the boat, or you mightn’t have been there at all, and then where would Cyril and I have been? ‘Fate holds the strings, and Men like children move but as they’re led: Success is from above.’”

A hansom cab pulled up beside us. “Tack ye summers, gemmun?” the driver said in a completely unintelligible accent.

Terence shook his head. “By the time we got all our luggage in, it’s faster to walk. And we’re nearly there.”

We were. There was Folly Bridge, and a tavern, and the river, with a ragtag of boats tied up to its edge.

“‘Fate, show thy force. What is decreed must be, and be this so,’” Terence said, crossing the bridge. “We go to meet our destiny.” He started down the steps toward the dock. “Jabez,” he called out to the man standing on the riverbank. “You haven’t rented our boat, have you?”

Jabez looked like something out of Oliver Twist He had a scruffy beard and a decidedly unfriendly manner. He was standing with his thumbs in a pair of impossibly dirty braces, and his hands were, if possible, even dirtier.

At his feet lay an enormous brown-and-white bulldog, its ugly flattened snout resting on its paws. Even at this distance, I could see its powerful shoulders and belligerent underslung jaw. Bill Sikes in Oliver Twist had had a bulldog, hadn’t he?

I didn’t see any sign of anyone who might be Terence’s friend Cyril, and I wondered if Jabez and his dog had murdered him and thrown him in the river.

Terence, obliviously chattering, hurried down the bank toward the boat. And the monster. I followed cautiously, keeping well to the rear and hoping it might ignore us like the hound at the station, but as soon as it saw us, it sat up alertly.

“Here we are,” Terence called out gaily, and the bulldog took off at a run for us.

I let go of the satchel and box with a thud, clapped the covered basket to my chest like a shield, and looked wildly about for a stick.

The bulldog’s wide mouth opened as he ran, revealing foot-long canines and row upon row of sharklike teeth. Bulldogs had been used for fighting in the Nineteenth Century, hadn’t they? Fighting bulls, that was how they’d gotten their name, wasn’t it? Leaping for the bull’s jugular and hanging on? That was how they’d gotten that mashed-in nose, too, and those heavy jowls, wasn’t it? The flat muzzle had been bred into them so they could breathe without letting go.

“Cyril!” Terence cried, but no one appeared to save us, and the bulldog shot past him and straight for me.

I dropped the covered basket, and it rolled off toward the riverbank. Terence dived for it. The bulldog paused and then took off for me again.

I had never understood what would hypnotize a rabbit into standing there and staring at an approaching snake, but now I realized it must be the snake’s unusual method of movement.

The bulldog was running straight toward me, but it was more a roll than a run, and there was a lateral component to it, so that although he was clearly going directly for my throat, he nevertheless was canting to the left, so much that I thought he might miss me altogether, and by the time I realized he wouldn’t, it was too late to run.

The bulldog flung himself at me and I went down, trying to protect my jugular with both hands and wishing I had been more sympathetic to Carruthers.

The bulldog had his front paws on my shoulders and his wide mouth inches from mine.

“Cyril!” Terence said, but I didn’t dare turn my head to see where he was. I hoped, wherever he was, that he had a weapon.

“Good boy,” I said to the bulldog, not very convincingly.

“This basket of yours nearly went in the drink,” Terence said, moving into my field of vision. “Best catch I’ve made since the match against Harrow in ’84.” He set the basket down on the ground beside me.

“Could you . . .” I said, cautiously taking one hand away from my neck to point at the bulldog.

“Oh, of course, how thoughtless of me,” Terence said. “You two haven’t been properly introduced.” He squatted down beside us. “This is Mr. Henry,” he said to the bulldog, “the newest member of our merry band and our financial savior.”

The bulldog opened his huge mouth in a wide, drooling grin.

“Ned,” Terence said, “allow me to introduce Cyril.”

“George said: ‘Let’s go up the river.’ He said we should have fresh air,

exercise and quiet; the constant change of scene would occupy our minds

(including what there was of Harris’s); and the hard work would give us a good appetite, and make us sleep well.”

Three Men in a Boat

Jerome K. Jerome

CHAPTER 5

Bulldogs’ Tenacity and Fierceness—Cyril’s Family Tree—More Luggage—Terence Packs—Jabez Packs—Riding a Horse—Christ Church Meadow—The Difference Between Poetry and Real Life—Love at First Sight—The Taj Mahal—Fate—A Splash—Darwin—A Rescue from a Watery Grave—An Extinct Species—Natural Forces—The Battle of Blenheim—

A Vision

How do you do, Cyril?” I said, not attempting to get up. I had read somewhere that any sudden movement could cause them to attack. Or was that bears? I wished Finch had brought me a tape on bulldogs instead of butlers. Bulldogs nowadays are solid marshmallow. Oriel’s mascot has a pleasant disposition and spends all of his time lying in front of the porter’s lodge, hoping someone will come along and pet him.

But this was a Nineteenth-Century bulldog, and the bulldog had originally been bred for bull-baiting, a charming sport in which bulldogs, specifically bred for tenacity and a ferocious disposition, latched onto vital arteries, and the bull, understandably annoyed, attempted to gore the dogs and/or toss them on his horns. When had bull-baiting been outlawed? Surely before 1888. But it would take some time, wouldn’t it, to breed all that tenacity and fierceness out of them?

“Delighted to make your acquaintance, Cyril,” I said hopefully.

Cyril made a sound that might have been a growl. Or a belch.

“Cyril comes from an excellent family,” Terence was saying, still squatting beside my prostrate form. “His father was Deadly Dan out of Medusa. His great-great-grandfather was Executioner. One of the great bull-baiters of all time. Never lost a fight.”

“Really?” I said weakly.

“Cyril’s great-great-great grandfather fought Old Silverback.” He shook his head in admiration. “Eight-hundred-pound grizzly bear. Latched onto his muzzle and didn’t let go for five hours.”

“But all that tenacity and fierceness has been bred out of them?” I said hopefully.

“Not at all,” Terence said.

Cyril growled again.

“I shouldn’t think they ever had it,” Terence continued, “except as an occupational necessity. Being clawed by a bear would make anyone ferocious, I should think. Wouldn’t it, Cyril?”

Cyril made the low rumble again, and this time it sounded definitely like a belch.

“A heart of gold Executioner had, so they say. Mr. Henry’s going on the river with us, Cyril,” he said, as if the bulldog didn’t still have me down and thoroughly drooled on, “as soon as we load the boat and settle up with Jabez.” He pulled out his pocket watch and snapped it open. “Come along, Ned. It’s nearly a quarter to twelve. You can play with Cyril later.” He picked up both bandboxes and started for the dock.

Passage

Passage Bellwether

Bellwether Blackout

Blackout Doomsday Book

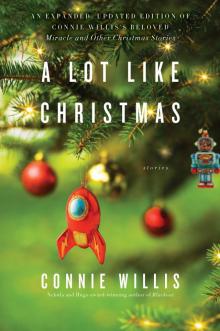

Doomsday Book A Lot Like Christmas: Stories

A Lot Like Christmas: Stories Water Witch

Water Witch To Say Nothing of the Dog

To Say Nothing of the Dog Fire Watch

Fire Watch The Winds of Marble Arch and Other Stories

The Winds of Marble Arch and Other Stories Uncharted Territory

Uncharted Territory All Clear

All Clear Crosstalk

Crosstalk Lincoln's Dreams

Lincoln's Dreams Miracle and Other Christmas Stories

Miracle and Other Christmas Stories Time is the Fire

Time is the Fire Blackout ac-1

Blackout ac-1 Dooms Day Book

Dooms Day Book Jack

Jack The Doomsday Book

The Doomsday Book Terra Incognita

Terra Incognita The Best of Connie Willis

The Best of Connie Willis Cibola

Cibola Schwarzschild Radius

Schwarzschild Radius Even the Queen

Even the Queen The Last of the Winnebagos

The Last of the Winnebagos Spice Pogrom

Spice Pogrom Oxford Time Travel 1 - Blackout

Oxford Time Travel 1 - Blackout At The Rialto

At The Rialto A Lot Like Christmas

A Lot Like Christmas