- Home

- Connie Willis

Dooms Day Book Page 9

Dooms Day Book Read online

Page 9

“He’s my great-nephew,” Mary said. “He was coming up on the tube to spend Christmas with me.”

“What time was the quarantine called?”

“Ten past three,” Mary said.

Dunworthy held up his hand to indicate he’d gotten through. “Is that Cornmarket Underground Station?” he said. It obviously was. He could see the gates and a lot of people behind an irritated-looking station master. “I’m phoning about a boy who came in on the tube at three o’clock. He’s twelve. He would have come in from London.” Dunworthy held his hand over the receiver and asked Mary, “What does he look like?”

“He’s blonde and has blue eyes. He’s tall for his age.”

“Tall,” Dunworthy said loudly over the sound of the crowd. “His name is Colin—”

“Templer,” Mary said. “Dierdre said he’d take the tube from Marble Arch at one.”

“Colin Templer. Have you seen him?”

“What the bloody hell do you mean have I seen him?” the stationmaster shouted. “I’ve got five hundred people in this station and you want to know if I’ve seen a little boy. Look at this mess.”

The visual abruptly showed a milling crowd. Dunworthy scanned it, looking for a tallish boy with blonde hair and blue eyes. It switched back to the station master.

“There’s just been a temp quarantine,” he shouted over the roar which seemed to get louder by the minute, “and I’ve got a station full of people who want to know why the trains have stopped and why don’t I do something about it. I’ve got all I can do to keep them from tearing the place apart. I can’t bother about a boy.”

“His name is Colin Templer,” Dunworthy shouted. “His great aunt was supposed to meet him.”

“Well, why didn’t she then and make one less problem for me to deal with? I’ve got a crowd of angry people here who want to know how long the quarantine’s going to last and why don’t I do something about that–” He cut off suddenly. Dunworthy wondered if he’d hung up or had the phone snatched out of his hand by an angry shopper.

“Had the stationmaster seen him?” Mary said.

“No,” Dunworthy said. “You’ll have to send someone after him.”

“Yes, all right. I’ll send one of the staff,” she said, and started out.

“The quarantine was called at 3:10, and he wasn’t supposed to get here till three,” Montoya said. “Maybe he was late.”

That hadn’t occurred to Dunworthy. If the quarantine had been called before his train reached Oxford, it would have been stopped at the nearest station and the passengers rerouted or sent back to London.

“Ring the station back,” he said, handing her the phone. He told her the number. “Tell them his train left Marble Arch at one. I’ll have Mary phone her niece. Perhaps Colin’s back already.”

He went out in the corridor, intending to ask the nurse to fetch Mary, but she wasn’t there. Mary must have sent her to the station.

There was no one in the corridor. He looked down it at the call box he had used before and then walked rapidly down to it and punched in Balliol’s number. There was an off-chance that Colin had gone to Mary’s rooms after all. He would send Finch round, and if Colin wasn’t there, down to the station. It would very likely take more than one person looking to find Colin in that mess.

“Hi,” a woman said.

Dunworthy frowned at the number in the inset, but he hadn’t misdialed. “I’m trying to reach Mr. Finch at Balliol College.”

“He’s not here right now,” the woman, obviously American, said. “I’m Ms. Taylor. Can I take a message?”

This must be one of the bellringers. She was younger than he’d expected, not much over thirty, and she looked rather delicate to be a bellringer. “Would you have him call Mr. Dunworthy at Infirmary as soon as he returns, please?”

“Mr. Dunworthy.” She wrote it down, and then looked up sharply. “Mr. Dunworthy,” she said in an entirely different tone of voice, “are you the person responsible for our being held prisoner here?”

There was no good answer to that. He should never have phoned the junior common room. He had sent Finch to the bursar’s office.

“The National Health Service issues temp quarantines in cases of an unidentified disease. It’s a precautionary measure. I’m sorry for any inconvenience it’s caused you. I’ve instructed my secretary to make your stay comfortable, and if there’s anything I can do for you—”

“Do? Do?! You can get us to Ely, that’s what you can do. My ringers were supposed to give a handbell concert at the cathedral at eight o’clock, and tomorrow we have to be in Norwich. We’re ringing a peal on Christmas Eve.”

He was not about to be the one to tell her they were not going to be in Norwich tomorrow. “I’m sure that Ely is already aware of the situation, but I will be more than happy to phone the cathedral and explain—”

“Explain! Perhaps you’d like to explain it to me, too. I’m not used to having my civil liberties taken away like this. In America, nobody would dream of telling you where you can or can’t go.”

And over ten million Americans died during the Pandemic as a result of that sort of thinking, he thought. “I assure you, Madam, that the quarantine is solely for your protection and that all of your concert dates will be more than willing to reschedule. In the meantime, Balliol is delighted to have you as our guests. I am looking forward to meeting you in person. Your reputation precedes you.”

And if that were true, he thought, I would have told you Oxford was under quarantine when you wrote for permission to come.

“There is no way to reschedule a Christmas Eve peal. We were to have rung a new peal, the Chicago Surprise Minor. The Norwich Chapter is counting on us to be there, and we intend—”

He hit the disconnect button. Finch was probably in the bursar’s office, looking for Badri’s medical records, but Dunworthy wasn’t going to risk getting another bell ringer. He looked up Regional Transport’s number instead and started to punch it in.

The door at the end of the corridor opened, and Mary came through it.

“I’m trying Regional Transport,” Dunworthy said, punching in the rest of the number and passing her the receiver.

She waved it away, smiling. “It’s all right. I’ve just spoken to Dierdre. Colin’s train was stopped at Barton. The passengers were put on the tube back to London. She’s going down to Marble Arch to meet him.” She sighed. “Dierdre didn’t sound very glad that he’s coming home. She planned to spend Christmas with her new livein’s family, and I think she rather wanted him out of the way, but it can’t be helped. I’m simply glad he’s out of this.”

He could hear the relief in her voice. He put the receiver back. “Is it that bad?”

“We just got the preliminary ident back. It’s definitely a Type A myxovirus. Influenza.”

He had been expecting something worse, some third world fever or a retrovirus. He had had the flu back in the days before antivirals. He had felt terrible, congested, feverish, achy, for a few days and then gotten over it without anything but bedrest and fluids.

“Will they call the quarantine off then?”

“Not until we get Badri’s medical records,” she said. “I keep hoping he skipped his last course of antivirals. If not, then we’ll have to wait till we locate the source.”

“But it’s only the flu.”

“If there’s a small antigenic shift, a point or two, it’s only the flu,” she corrected him. “If there’s a large shift, it’s influenza, which is an entirely different matter. The Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918 was a myxovirus. It killed twenty million people. Viruses mutate every few months. The antigens on their surface change so that they’re unrecognizable to the immune system. That’s why seasonals are necessary. But they can’t protect against a large point shift.”

“And that’s what this is?”

“I doubt it. Major mutations only happen every ten years or so. I think it’s more likely that Badri failed to get his seasonals. D

o you know if he was running an on-site at the beginning of term?”

“No. He may have been.”

“If he was, he may simply have forgotten to go in for them, in which case all he has is this winter’s flu.”

“What about Kivrin? Has she had her seasonals?”

“Yes, and full-spectrum antivirals and T-cell enhancement. She’s fully protected.”

“Even if it’s influenza?”

She hesitated a fraction of a second. “If she was exposed to the virus through Badri this morning, she’s fully protected.”

“And if she saw him before then?”

“If I tell you this, you’ll only worry, and I’m certain there’s no need to.” She took a breath. “The enhancement and the antivirals were given so that she would have peak immunity at the beginning of the drop.”

“And Gilchrist moved the drop up by two days,” Dunworthy said bitterly.

“I wouldn’t have allowed her to go through if I hadn’t thought it was all right.”

“But you hadn’t counted on her being exposed to an influenza virus before she even left.”

“No, but it doesn’t change anything. She has partial immunity, and we’re not certain she was even exposed. Badri scarcely went near her.”

“And what if she was exposed earlier?”

“I knew I shouldn’t have told you,” Mary said. She sighed. “Most myxoviruses have an incubation period of from twelve to forty-eight hours. Even if Kivrin was exposed two days ago, she’d have had enough immunity to prevent the virus from replicating sufficiently to cause anything but minor symptoms. But it’s not influenza.” She patted his arm. “And you’re forgetting the paradoxes. If she’d been exposed, she’d have been highly contagious. The net would never have let her through.”

She was right. Diseases couldn’t go through the net if there was any possibility of the contemps contracting them. The paradoxes wouldn’t allow it. The net wouldn’t have opened.

“What are the chances of the population in 1320 being immune?” he asked.

“To a modern-day virus? Almost none. There are eighteen hundred possible mutation points. The contemps would have all had to have had the exact virus, or they’d be vulnerable.”

Vulnerable. “I want to see Badri,” he said. “When he came to the pub, he said there was something wrong. He kept repeating it in the ambulance on the way to the hospital.”

“Something is wrong,” Mary said. “He’s got a serious viral infection.”

“Or he knows he exposed Kivrin. Or he didn’t get the fix.”

“He said he got the fix.” She looked sympathetically at him. “I suppose it’s useless to tell you not to worry about Kivrin. You saw how I’ve just acted over Colin. But I meant it when I said they’re both safer out of this. Kivrin’s much better off where she is than she would be here, even among those cutthroats and thieves you persist in imagining. At least she won’t have to deal with NHS quarantine regulations

He smiled. “Or American change ringers. America hadn’t been discovered yet.” He reached for the door handle.

The door at the end of the corridor banged open and a large woman carrying a valise barged through it. “There you are, Mr. Dunworthy,” she shouted the length of the corridor. “I’ve been looking everywhere for you.”

“Is that one of your bell ringers?” Mary said, turning to look down the corridor at her.

“Worse,” Dunworthy said. “It’s Mrs. Gaddson.”

Chapter Six

It was growing dark under the trees and at the bottom of the hill. Kivrin’s head began to ache before she had even reached the frozen wagon ruts, as if it had something to do with microscopic changes in altitude or light.

She couldn’t see the wagon at all, even standing directly in front of the little chest, and squinting into the darkness past the thicket made her head feel even worse. If this was one of the “minor symptoms” of time-lag, she wondered what a major one would be like.

When I get back, she thought, struggling through the thicket, I intend to have a little talk with Dr. Ahrens on the subject. I think they are underestimating the debilitating effects these minor symptoms can have on an historian. Walking down the hill had left her more out of breath than climbing it had, and she was so cold.

Her cloak and then her hair caught on the willows as she pushed her way through the thicket, and she got a long scratch on her arm that immediately began to ache, too. She tripped once and nearly fell flat, and the effect on her headache was to jolt it so that it stopped hurting and then returned with redoubled force.

It was almost completely dark in the clearing, though what little she could see was still very clear, the colors not so much fading as deepening toward black—black-green and black-brown and black-gray. The birds were settling in for the night. They must have got used to her. They didn’t so much as pause in their pre– bedtime twitterings and settlings down.

Kivrin hastily grabbed up the scattered boxes and splintered kegs, and flung them into the tilting wagon. She took hold of the wagon’s tongue and began to pull it toward the road. The wagon scraped a few inches, slid easily across a patch of leaves, and stuck. Kivrin braced her foot and pulled again. It scraped a few more inches and tilted even more. One of the boxes fell out.

Kivrin put it back in and walked around the wagon, trying to see where it was stuck. The right wheel was jammed against a tree root, but it could be pushed up and over, if only she could get a decent purchase. She couldn’t on this side—Mediaeval had taken an ax to this side so that it would look like the wagon had been smashed when it overturned, and they had done a good job. It was nothing but splinters. I told Mr. Gilchrist he should have let me have gloves, she thought.

She came around to the other side, took hold of the wheel, and shoved. It didn’t budge. She pulled her skirts and cloak out of the way and knelt beside the wheel so she could put her shoulder to it.

The footprint was in front of the wheel, in a little space swept bare of leaves and only as wide as the foot. The leaves had drifted up against the roots of the oaks on either side. The leaves did not hold a print that she could see in the graying light, but the print in the dirt was perfectly clear.

It can’t be a footprint, Kivrin thought. The ground is frozen. She reached out to put her hand in the indentation, thinking it might be some trick of shadow or the failing light. The frozen ruts out in the road would not have taken any print at all. But the dirt gave easily under her hand, and the print was deep enough to feel.

It had been made by a soft-soled shoe with no heel, and the foot that had made it was large, larger even than hers. A man’s foot, but men in the 1300’s had been smaller, shorter, with feet not even as big as hers. A giant’s foot.

Maybe it’s an old footprint, she thought wildly. Maybe it’s the footprint of a woodcutter, or a peasant looking for a lost sheep. Maybe this is one of the king’s woodlands, and they’ve been through here hunting. But it wasn’t the footprint of someone chasing a deer. It was the print of someone who had stood there for a long time, watching her. I heard him, she thought, and a little flutter of panic forced itself up into her throat. I heard him standing there.

She was still kneeling, holding onto the wheel for balance. If the man, whoever it was, and it had to be a man, a giant, were still here in this glade, watching, he must know that she had found the footprint. She stood up. “Hello!” she called, and frightened the birds to death again. They flapped and squawked themselves into hushed silence. “Is someone there?”

She waited, listening, and it seemed to her that in the silence she could hear the breathing again. “Speke. I am in distresse an my servauntes fled.”

Lovely, she thought even as she said it. Tell him you’re helpless and all alone.

“Halloo!” she called again and began a cautious circuit of the glade, peering out into the trees. If he was still standing there, it was so dark she wouldn’t be able to see him. She couldn’t make out anything past the edges of the

glade. She couldn’t even tell for sure which way the thicket and the road lay. If she waited any longer, it would be completely dark, and she would never be able to get the wagon to the road.

But she couldn’t move the wagon. Whoever had stood there between the two oaks, watching her, knew that the wagon was here. Maybe he had even seen it come through, bursting on the sparkling air like something conjured by an alchemist. If that were the case, he had probably run off to get the stake Dunworthy was so sure the populace kept in readiness. But surely if that were the case he would have said something, even if it was only, “Yoicks!” or “Heavenly Father!” and she would have heard him crashing through the underbrush as he ran way.

He hadn’t run away, though, which meant he hadn’t seen her come through. He had come upon her afterwards, lying inexplicably in the middle of the woods beside a smashed wagon, and thought what? That she had been attacked on the road and then dragged here to hide the evidence?

Then why hadn’t he tried to help her? Why had he stood there, silent as an oak, long enough to leave a deep footprint, and then gone away again? Maybe he had thought she was dead. He would have been frightened of her unshriven body. People as late as the fifteenth century had believed that evil spirits took immediate possession of any body not properly buried.

Or maybe he had gone for help, to one of those villages that Kivrin had heard, maybe even Skendgate, and was even now on his way back with half the town, all of them carrying lanterns.

In that case, she should stay where she was and wait for him to come back. She should even lie down again. When the townspeople arrived, they could speculate about her and then bear her to the village, giving her examples of the language, the way her plan had been intended to work in the first place. But what if he came back alone, or with friends who had no intention of helping her?

She couldn’t think. Her headache had spread out from her temple to behind her eyes. As she rubbed her forehead, it began to throb. And she was so cold! This cloak, in spite of its rabbit-fur lining, wasn’t warm at all. How had people survived the Little Ice Age dressed only in cloaks like this? How had the rabbits survived?

Passage

Passage Bellwether

Bellwether Blackout

Blackout Doomsday Book

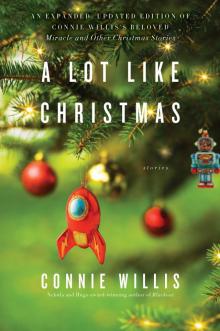

Doomsday Book A Lot Like Christmas: Stories

A Lot Like Christmas: Stories Water Witch

Water Witch To Say Nothing of the Dog

To Say Nothing of the Dog Fire Watch

Fire Watch The Winds of Marble Arch and Other Stories

The Winds of Marble Arch and Other Stories Uncharted Territory

Uncharted Territory All Clear

All Clear Crosstalk

Crosstalk Lincoln's Dreams

Lincoln's Dreams Miracle and Other Christmas Stories

Miracle and Other Christmas Stories Time is the Fire

Time is the Fire Blackout ac-1

Blackout ac-1 Dooms Day Book

Dooms Day Book Jack

Jack The Doomsday Book

The Doomsday Book Terra Incognita

Terra Incognita The Best of Connie Willis

The Best of Connie Willis Cibola

Cibola Schwarzschild Radius

Schwarzschild Radius Even the Queen

Even the Queen The Last of the Winnebagos

The Last of the Winnebagos Spice Pogrom

Spice Pogrom Oxford Time Travel 1 - Blackout

Oxford Time Travel 1 - Blackout At The Rialto

At The Rialto A Lot Like Christmas

A Lot Like Christmas