- Home

- Connie Willis

A Lot Like Christmas Page 7

A Lot Like Christmas Read online

Page 7

“Dr. Oakes and his niece. They didn’t want to meet Shiloh and Justin. They want to see Only Human. And to meet you.”

I’ll bet, I thought, waiting for Torrance to get to the real reason he’d come backstage to see me, because meeting a couple of fans couldn’t be it. He dragged a ragtag assortment of people backstage every week. He wasn’t still trying to talk me into doing the latest revival of Cats, was he? It was not only the worst musical ever produced on Broadway, but it required tights and whiskers.

“Dr. Oakes’s niece is really eager to meet you,” Torrance was saying. “She’s a huge fan of yours. It will only take five minutes,” he pleaded. “And it would really help with ticket sales.”

“Why do the ticket sales need help? I thought you said we had full houses through Christmas.”

“We do, but the weather’s supposed to turn bad next week, and sales for after New Year’s have been positively limp. Management’s worried we won’t last through January. And the word is Disney’s scouting for a theater where they can put a new production of Tangled. If they get nervous about our closing—”

“I don’t see how meeting them will help us get publicity. Physicists are hardly front-page news.”

“I can guarantee it’ll get us publicity. WNET’s already said they’ll be here to live-stream it. And Sirius. And when Emily said she wanted to meet you on Good Morning, America yesterday, ticket sales for this weekend went through the roof.”

“I thought you said we were already sold out through Christmas.”

“I said Only Human was playing to full houses.”

Which meant half the tickets were going for half price at the TKTS booth in Times Square and the back five rows of the balcony were roped off for “repairs.”

“And you know what the management’s like when they think they’re going to lose their investment. They’ll jump at anything—”

“All right,” I said. “I’ll meet with Dr. Nobel Prize and his niece, if she is his niece. Which I seriously doubt.”

“Why do you say that?” Torrance said sharply.

“Because all middle-aged men are alike, even scientists. Her name wouldn’t be Miss Caswell, would it?”

“Who?”

“The producer’s girlfriend,” I said. I pantomimed a pair of enormous breasts. “Ring a bell?” He looked blank. “Really, Torrance, you should at least pretend to have watched the plays I’m starring in.”

“I do. I have. I just don’t remember any Miss Caswell in Only Human.”

“That’s because she wasn’t in Only Human. She was in Bumpy Night. Lindsay Lohan played her, remember?” and when he still looked blank, “Marilyn Monroe played her in the original movie. And please don’t tell me you don’t know who that is, or you’ll make me feel even more ancient than I am.”

“You’re not ancient, dear one,” he said, “and I wish you’d stop being so hard on yourself. You’re a legend.”

Which is a word even more deadly to one’s career than “old” or “cellulite.” And only slightly less career-ending than “First Lady of the Theater.” I said, “Yes, well, this ‘legend’ just changed her mind. No backstage interview.”

“Okay,” he said. “I’ll tell them no dice. But don’t be surprised if they decide to go to Forbidden Planet instead. Their entire cast has agreed to a backstage interview, including Justin.”

“All right, fine. I’ll do it,” I said. “If you get me out of the lunch with Nusbaum and talk to Austerman about Desk Set.”

“I will. This interview will help on the Desk Set thing,” he said, though I couldn’t see how. “Star Meets Fans” is hardly home-page news. “You’ll be glad you did this. You’re going to like Emily.”

There was only one thing to like about having been blackmailed into doing the interview: our discussion of it had taken up the entire intermission, and Torrance hadn’t had time to ask me the thing he’d actually come backstage to.

I expected him to try again after the show, but he didn’t. He left a message saying, “WABC will be there to film meeting. Wear something suitable for Broadway legend. Sunset Boulevard?” Which was proof either that he saw me much as I was beginning to see myself, as a fading (and deranged) star, or that he hadn’t seen the musical Sunset Boulevard, either.

I had the wardrobe mistress hunt me up the magenta hostess gown from Mame and a pair of Evita earrings, signed autographs for the fans waiting outside the stage door, turned my phone off, and went home to bed.

I kept my phone off through Thanksgiving Day so Torrance couldn’t call me and insist I watch Dr. Oakes in the parade, but I didn’t want to miss a possible call from Austerman about Desk Set, so Friday I turned my phone back on, assuming (incorrectly) that Torrance would immediately call and make another attempt at broaching the subject of whatever it was he’d really come to my dressing room about.

Because it couldn’t possibly be the scruffy-looking professor and his all-dressed-up niece who Torrance brought to my dressing room Friday night after the show. I could see why Torrance had rejected the idea of her being the producer’s mistress. This petite, fresh-scrubbed teenager with her light brown hair and upturned nose and pink cheeks was nothing like Marilyn Monroe. She was nothing like the gangly, tattooed, tipped, and tattered girls who clustered outside Forbidden Planet every night either, waiting for Justin Jr. to autograph their Playbills.

This girl, who couldn’t be more than five foot two, looked more like the character of Peggy in the first act of 42nd Street, wide-eyed and giddy at being in New York City for the first time. Or a sixteen-year-old Julie Andrews. The sort of dewy-eyed innocent ingénue that every established actress hates on sight. And that the New York press can’t wait to get its claws into.

But they were being oddly deferential. And they were all here. Not just Good Morning America, but the other networks, the cable channels, the Times, the Post–Daily News, and at least a dozen bloggers and streamers.

“How’d you manage to pull this off?” I whispered to Torrance as they squeezed into my dressing room. Apart from the Tonys, Spiderman III accidents, and Hollywood stars, it’s impossible to get the media to cover anything theatrical. “Lady Gaga’s not replacing me in the role, is she?”

He ignored that. “Claire, dear one,” he said, as if he were in a production of Noël Coward’s Private Lives, “allow me to introduce Dr. Edwin Oakes. And this,” he said, presenting the niece to me with a flourish, “is Emily.”

“Oh, Miss Havilland,” she said eagerly. “It’s so exciting to meet you. You were just wonderful.”

Well, at least she hadn’t said it was an honor to meet me, or called me a legend.

“I loved Only Human,” she said. “It’s the best play I’ve ever seen.”

It was probably the only play she’d ever seen, but Torrance had been right, this meeting would be good publicity. The media were recording every word and obviously responding to Emily’s smile, which even I had to admit was rather sweet.

“You sing and dance so beautifully, Miss Havilland,” she said. “And you make the audience believe that what they’re seeing is real—”

“You’re Emily’s favorite actress,” Torrance cut in. “Isn’t that right, Emily?”

“Oh, yes. I’ve seen all your plays—Feathers and Play On! and The Drowsy Chaperone and Fender Strat and Anything Goes and Love, Etc.”

“But I thought Torrance said this was your first time in New York,” I said. And she was much too young to have seen Play On! She’d have been five years old.

“It is my first time,” she said earnestly. “I haven’t seen the plays onstage, but I’ve seen all your filmed performances and the numbers you’ve done at the Tony Awards—‘When They Kill Your Dream’ and ‘The Leading Lady’s Lament.’ And I’ve watched your interviews on YouTube and read all your online interviews and listened to the soundtracks of A Chorus Line and Tie Dye and In Between the Lines.”

“My, you are a fan!” I said. “Are you sure your name’s Emily an

d not Eve?”

“Eve?” Dr. Oakes said sharply.

Torrance shot me a warning glance, and the reporters all looked up alertly from the Androids they were taking notes on. “Why would you think her name was Eve, Miss Havilland?” one of them asked.

“I was making a joke,” I said, taken aback at all this reaction. And if I said it was a reference to Eve Harrington, none of them would have ever heard of her, and if I said she was a character in Bumpy Night, none of them would have heard of that, either. “I…”

“She called me Eve because I was doing what Eve Harrington did,” Emily said. “That’s who you meant, isn’t it, Miss Havilland? The character in the musical Bumpy Night?”

“I…y-yes,” I stammered, trying to recover from the shock that she’d recognized the allusion. The younger generation’s knowledge usually doesn’t extend further back than High School Musical: The Musical.

“When Eve meets the actress Margo Channing,” Emily was cheerfully telling the reporters, “she gushes to her about what a wonderful actress she is.”

“Bumpy Night?” one of the reporters said, looking as lost as Torrance usually does.

“Yes,” Emily said. “The musical was based on the movie All About Eve, which starred Bette Davis and Anne Baxter.”

“And Marilyn Monroe,” I said.

“Right,” Emily said, dimpling. “As Miss Caswell, the producer’s girlfriend. It was her screen debut.”

I was beginning to like this girl, in spite of her perfect skin and perfect hair and the way she could hold an audience. The media were hanging on her every word. Although that might be because they were as astonished as I was at a teenager’s knowledge of the movie.

“Marilyn Monroe—she was in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes and How to Marry a Millionaire,” she said, “which Lauren Bacall was in, too. She starred in the first musical they made of All About Eve: Applause. It wasn’t nearly as good as Bumpy Night, or as faithful to the movie.”

And since she knew so much about movies, maybe this was a good time to put in a pitch for my doing Austerman’s play. “Have you ever seen Desk Set, Emily?” I asked her.

“Which one? The Julia Roberts–Richard Gere remake or the original with Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy?”

Good God. “The original.”

“Yes, I’ve seen it. I love that movie.”

“So do I,” I said. “Did you know they’re thinking of making a musical of it?”

“Oh, you’d be wonderful in the Katharine Hepburn part!”

I definitely liked this girl.

“What about Cats?” Torrance asked.

I glared at him, but he ignored me.

“Have you ever seen the musical Cats?” he persisted.

“Yes,” she said, and wrinkled her nose in distaste. “I didn’t like it. There’s no plot at all, and ‘Memory’ is a terrible song. Cats isn’t nearly as good as Only Human.”

“You see, Torrance?” I said, and turned my widest smile on Emily. “I’m so glad you came to the show tonight.”

“So am I,” she said. “I’m sorry I sounded like Eve Harrington before. I wouldn’t want to be her. She wasn’t a nice person,” she explained to the reporters. “She tried to steal Margo’s part in the play from her.”

“You’re right, she wasn’t very nice,” I said. “But I suppose one can’t blame her for wanting to be an actress. After all, acting’s the most rewarding profession in the world. What about you, Emily? Do you want to be an actress?”

It should have been a perfectly safe question. Every teenage girl who’s ever come backstage to meet me has been seriously stagestruck, especially after seeing her first Broadway musical, and Emily had to be, given her obsessive interest in the movies and my plays.

But she didn’t breathe “Oh, yes,” like every other girl I’d asked. She said, “No, I don’t.”

You’re lying, I thought.

“I could never do what you do, Miss Havilland,” Emily went on in that matter-of-fact voice.

“Then what do you want to do? Paint? Write?”

She glanced uncertainly at her uncle and then back at me.

“Or does your uncle want you to be a neurophysicist like him?” I asked.

“Oh, no, I couldn’t do that, either. Any of those things.”

“Of course you could, an intelligent girl like you. You can do anything you want to do.”

“But I—” Emily glanced at her uncle again, as if for guidance.

“Come, you must want to be something,” I said. “An astronaut. A ballerina. A real boy.”

“Claire, dear one, stop badgering the poor child,” Torrance said with an artificial-sounding laugh. “She’s in New York for the very first time. It’s scarcely the time for career counseling.”

“You’re right. I’m sorry, Emily,” I said. “How are you liking New York?”

“Oh, it’s wonderful!” she said.

The eagerness was back in her voice, and Dr. Oakes had relaxed. Did she want to go on the stage and her uncle didn’t approve? Or was something else going on? “How are you liking New York?” was hardly riveting stuff, but there wasn’t a peep out of the media. They were watching us raptly, as if they expected something to happen at any second.

I should have read the article in the Times, I thought, and asked Emily if she’d been to the Empire State Building yet.

“No,” she said, “we do that tomorrow morning after we do NBC Weekend, and then at ten I’m going ice-skating at Rockefeller Center. It would be wonderful if you could come, too.”

“At ten in the morning?” I said, horrified. “I’m not even up by then,” and the reporters laughed. “Thank you for asking me, though. What are you doing tomorrow night?” I asked, and then realized she was likely to say, “We’re seeing Forbidden Planet,” but I needn’t have worried.

“We’re going to see the Christmas show at Radio City Music Hall,” she said.

“Oh, good. You’ll love the Rockettes. Or have you seen them already? They were in the parade, weren’t they?”

“No,” Emily said. “What are—?”

“They don’t ride in the parade,” Torrance said, cutting in. “They dance outside Macy’s on Thirty-fourth Street. What else are you and your uncle doing tomorrow, Emily?”

“We’re going to Times Square, and then Macy’s and Bloomingdale’s to see the Christmas windows, and then the Disney store—”

“Good God,” I said. “All in one day? It sounds exhausting!”

“But I don’t—” Emily began.

This time it was Dr. Oakes who cut in. “She’s too excited at being here to be tired,” he said. “There’s so much to see and do. Emily’s really looking forward to seeing the Rockettes, aren’t you?” He nodded at her, as if giving her a cue, and the reporters leaned forward expectantly. But they weren’t looking at her, they were looking at me.

And suddenly it all clicked into place—their wanting to avoid the subject of her being tired, and Torrance’s wanting to know what I’d read about the parade, and Emily’s encyclopedic knowledge of plays, and the Wall-E balloon.

The parade’s robot theme wasn’t in honor of Forbidden Planet. It was in honor of Dr. Oakes and his “artificials,” one of which was standing right in front of me. And those cheeks were produced by sensors; that wide-eyed look and dimpled smile were programmed in.

Torrance, the little rat, had set me up. He’d counted on the fact that I only read Variety and wouldn’t know who Emily was.

And no wonder the media was all here. They were waiting with bated breath for the moment when I realized what was going on. It would make a great YouTube video—my shocked disbelief, Dr. Oakes’s self-satisfied smirk, Torrance’s laughter.

And if I hadn’t tumbled to it, and she’d managed to fool me all the way to the end of the interview with me none the wiser, so much the better. It would be evidence of what Dr. Oakes was obviously here to prove—that his artificials were indistinguishable from humans.

&nb

sp; Emily really is Eve Harrington, I thought. Innocent and sweet and vulnerable-looking. And not at all what she appears to be.

But if I said that, if I suddenly pointed an accusing finger at her and shouted, “Impostor!” it would blow the image Dr. Oakes and AIS were trying to promote and make Torrance furious. And, from what I’d seen so far, Emily might be capable of bursting into authentic-looking tears, and I’d end up looking like a bully, just like Margo Channing had at the party at the end of Act One of Bumpy Night, and there would go any chance I had of getting the lead in Desk Set.

But if I went on pretending I hadn’t caught on and continued playing the part Torrance had cast me in in this little one-act farce, I’d look like a prize fool. I could see the headline crawl on the Times building in Times Square now: “Bumpy Night for Broadway Legend.” And “Robot Fools First Lady of the Theater.” Not exactly the sort of publicity that gets an actress considered for a Tony.

Plus, the entire point of Desk Set was that humans are smarter than technology. What would Katharine Hepburn do in this situation? I wondered. Or Margo Channing?

“You’ll love the Christmas show,” Torrance was saying. “Especially the Nativity scene. They have real donkeys and sheep. And camels.”

“I’m sure it will be wonderful,” Emily said, smiling winsomely over at me, “but I don’t see how it can be any better than Only Human.”

Only human. Of course. That was why they’d wanted to see the play and come backstage to trick me. Fasten your seat belts, I said silently. It’s going to be a bumpy night.

“And you’ll love Radio City Music Hall itself,” Torrance said. “It’s this beautiful Art Deco building.”

Dr. Oakes nodded. “They’ve offered to give us a tour before the show, haven’t they, Emily?”

This was my cue. “Emily,” I repeated musingly. “That’s such a pretty name. You never hear it anymore. Were you named after someone?”

The reporters looked up as one from their corders and Androids, and Dr. Oakes tensed visibly. Which meant I was right.

“Yes,” Emily said. “I was named after Emily Webb from—”

“Our Town,” I said, thinking, Of course. It was perfect. Except for Little Eva in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Emily Webb was the most sickeningly sweet ingénue to ever grace the American stage, tripping girlishly around in a white dress with a big bow in her hair and prattling about how much she loves sunflowers and birthdays and “sleeping and waking up,” and then dying tragically at the beginning of Act Three.

Passage

Passage Bellwether

Bellwether Blackout

Blackout Doomsday Book

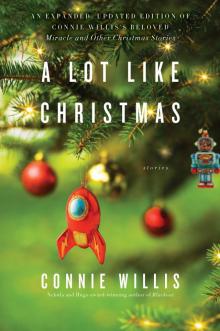

Doomsday Book A Lot Like Christmas: Stories

A Lot Like Christmas: Stories Water Witch

Water Witch To Say Nothing of the Dog

To Say Nothing of the Dog Fire Watch

Fire Watch The Winds of Marble Arch and Other Stories

The Winds of Marble Arch and Other Stories Uncharted Territory

Uncharted Territory All Clear

All Clear Crosstalk

Crosstalk Lincoln's Dreams

Lincoln's Dreams Miracle and Other Christmas Stories

Miracle and Other Christmas Stories Time is the Fire

Time is the Fire Blackout ac-1

Blackout ac-1 Dooms Day Book

Dooms Day Book Jack

Jack The Doomsday Book

The Doomsday Book Terra Incognita

Terra Incognita The Best of Connie Willis

The Best of Connie Willis Cibola

Cibola Schwarzschild Radius

Schwarzschild Radius Even the Queen

Even the Queen The Last of the Winnebagos

The Last of the Winnebagos Spice Pogrom

Spice Pogrom Oxford Time Travel 1 - Blackout

Oxford Time Travel 1 - Blackout At The Rialto

At The Rialto A Lot Like Christmas

A Lot Like Christmas