- Home

- Connie Willis

To Say Nothing of the Dog Page 5

To Say Nothing of the Dog Read online

Page 5

Mr. Dunworthy leaned forward and put his spectacles on. “Has there been an increase in slippage?”

“No. Lady Schrapnell simply has no concept of the workings of time travel. She—”

“The field of marrows,” I said.

“What?” Mr. Chiswick turned and glared at me.

“The farmer’s wife thought he was a German paratrooper.”

“Paratrooper?” Chiswick said, and his eyes narrowed. “You’re not the missing historian, are you? What’s your name?”

“John Bartholomew,” Mr. Dunworthy said.

“Whom, I see from his condition, Lady Schrapnell has recruited. She must be stopped, Dunworthy” The handheld began bleeping and spitting again. He read aloud. “‘No info yet on Henry’s whereabouts. Why not? Send location immediately. Need two more people to go to Great Exhibition, 1850, check on possible origins of bishop’s bird stump.’” He crumpled the readout and threw it on Mr. Dunworthy’s desk. “You’ve got to do something about her now! Before she destroys the university!” he said, and swept out.

“Or the known universe,” Mr. Dunworthy murmured.

“Should I go after him?” Finch asked.

“No,” Mr. Dunworthy said. “Try to get in touch with Andrews, and call up the Bodleian’s files on parachronistic incongruities.”

Finch went out. Mr. Dunworthy took off his spectacles and peered through them, frowning.

“I know this is a bad time,” I said, “but I wondered if you had any idea where I might be able to go to convalesce. Away from Oxford.”

“Meddling,” Mr. Dunworthy said. “Meddling got us into this, and more meddling will only make it worse.” He put his spectacles back on and stood up. “Clearly the best thing to do is wait and see what happens, if anything,” he said, pacing. “The chances that its disappearance would affect history are statistically insignificant, particularly from that era. Whole batches of them were routinely thrown in rivers to keep the numbers down.”

The number of fans? I thought.

“And the fact that it came through the net is in itself a proof that it didn’t create an incongruity, or the net wouldn’t have opened.” He wiped his spectacles on the tail of his jacket and held them up to the light. “It’s been over a hundred and fifty years. If it were going to destroy the universe, it would very likely have done so by now.”

He exhaled onto the lenses and wiped them again. “And I refuse to believe that there are two courses of history in which Lady Schrapnell and her project to rebuild Coventry Cathedral could exist.”

Lady Schrapnell. She’d be back from the Royal Masonic any time now. I leaned forward in the chair. “Mr. Dunworthy,” I said, “I was hoping you could think of somewhere where I could recover from the time-lag.”

“On the other hand, there’s a good chance that the reason there wasn’t an incongruity is that it was returned before there could be any consequences, disastrous or otherwise.”

“The nurse said two weeks’ bed rest, but if I could just get three or four days—”

“But even if that is the case,” he stood up and began pacing, “there’s still no reason not to wait. That’s the beauty of time travel. One can wait three or four days, or two weeks, or a year, and still return it immediately.”

“If Lady Schrapnell finds me—”

He stopped pacing and stared at me. “I hadn’t thought about that. Oh, Lord, if Lady Schrapnell were to find out about it—”

“If you could just suggest somewhere quiet and out of the way—”

“Finch!” Mr. Dunworthy shouted, and Finch came in from the outer office, carrying a readout.

“Here’s the bibliography on parachronistic incongruities,” he said. “There wasn’t much. Mr. Andrews is in 1560. Lady Schrapnell sent him there to examine the clerestory arches. Should I try to get Mr. Chiswick back here?”

“First things first,” Mr. Dunworthy said. “We need to find Ned here a place where he can rest and recuperate from his time-lag without interruption.”

“Lady Schrapnell—” I said.

“Exactly,” Mr. Dunworthy said. “It can’t be anywhere in this century. Or the Twentieth Century. And it needs to be somewhere peaceful and out of the way, a country house, perhaps, on a river. The Thames.”

“You’re not thinking of—” Finch said.

“He needs to leave immediately,” Mr. Dunworthy said. “Before Lady Schrapnell finds out about it.”

“Oh!” Finch gasped. “Yes, I see. But Mr. Henry’s in no condition to—” Finch said, but Mr. Dunworthy cut him off.

“Ned,” he said to me, “how would you like to go to the Victorian era?”

The Victorian era. Long dreamy afternoons boating on the Thames and playing croquet on emerald lawns with girls in white frocks and fluttering hair ribbons. And later, tea under the willow tree, served in delicate Sevres cups by bowing butlers, anxious to minister to one’s every whim, and those same girls, reading aloud from a slim volume of poetry, their voices floating like flower petals on the scented air. “All in the golden afternoon, where Childhood’s dreams are twined, In Memory’s mystic band—”

Finch shook his head. “I don’t think this is a good idea, Mr. Dunworthy.”

“Nonsense,” Mr. Dunworthy said. “Listen to him. He’ll fit right in.”

“. . . when you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains,

however improbable, must be the truth.”

Sherlock Holmes

CHAPTER 3

A Straightforward Job—Angels, Archangels, Cherubim, Powers, Thrones, Dominions, and the Other One—Drowsiness—I Am Prepped in Victorian History and Customs—Luggage—The Inspiring Story of Ensign Klepperman—More Luggage—Difficulty in Distinguishing Sounds—Fish Forks—Sirens, Sylphs, Nymphs, Dryads, and the Other One—An Arrival—Dogs Not Man’s Best Friend—Another Arrival—An Abrupt Departure

Do you think that’s a good idea?” Finch said. “He’s already suffering from advanced time-lag. Won’t that large a jump—?”

“Not necessarily,” Mr. Dunworthy said. “And after he’s completed his assignment, he can stay as long as he needs to to recover. You heard him, it’s a perfect holiday spot.”

“But in his condition, do you think he’ll be able to—” Finch said anxiously.

“It’s a perfectly straightforward job,” Mr. Dunworthy said. “A child could do it. The important thing is that it be done before Lady Schrapnell gets back, and Ned’s the only historian in Oxford who’s not off somewhere chasing after misericords. Take him over to the net and then ring up Time Travel and tell Chiswick to meet me there.”

The telephone bipped, and Finch answered it, then listened for a considerable length of time. “No, he was at the Royal Free,” he said finally, “but they decided to run a TWR, so they had to transport him to St. Thomas’s. Yes, in Lambeth Palace Road.” He listened again, holding the receiver some distance from his ear. “No, this time I’m certain.” He rang off. “That was Lady Schrapnell,” he said unnecessarily. “I’m afraid she may be returning soon.”

“What’s a TWR?” Mr. Dunworthy said.

“I invented it. I think Mr. Henry had best get over to the net to be prepped.”

Finch walked me over to the lab, which I was grateful for, especially as it seemed to me we were going completely the wrong direction, though when we got there, the door looked the same, and there was the same group of SPCC picketers outside.

They were carrying electric placards that read, “What’s wrong with the one we already have?” “Keep Coventry in Coventry,” and “It’s Ours!” One of them handed me a flyer that began, “The restoration of Coventry Cathedral will cost fifty billion pounds. For the same amount of money, the present Coventry Cathedral could not only be bought back and restored, but a new, larger shopping center could be built to replace it.”

Finch pulled the tract out of my hand, gave it back to the picketer, and opened the door.

The net looked the same inside, too, t

hough I didn’t recognize the pudgy young woman at the console. She was wearing a white lab coat, and her halo of cropped blonde hair made her look like a cherub rather than a net technician.

Finch shut the door behind us, and she whirled. “What do you want?” she demanded.

Perhaps more an archangel than a cherub.

“We need to arrange for a jump,” Finch said. “To Victorian England.”

“Out of the question,” she snapped.

Definitely an archangel. The sort that tossed Adam and Eve out of the Garden.

Finch said, “Mr. Dunworthy authorized it, Miss . . .”

“Warder,” she snapped.

“Miss Warder. This is a priority jump,” he said.

“They’re all priority jumps. Lady Schrapnell doesn’t authorize any other sort.” She picked up a clipboard and brandished it at us like a flaming sword. “Nineteen jumps, fourteen of them requiring 1940 ARP and WVS uniforms, which the wardrobe department is completely out of, and all the fixes. I’m three hours behind schedule on rendezvouses, and who knows how many more priority jumps Lady Schrapnell will come up with before the day’s over.” She slammed the clipboard down. “I don’t have time for this. Victorian England! Tell Mr. Dunworthy it’s completely out of the question.” She turned back to the console and began hitting keys.

Finch, undaunted, tried another tack. “Where’s Mr. Chaudhuri?”

“Exactly,” she said, whirling round again. “Where is Badri, and why isn’t he here running the net? Well, I’ll tell you.” She picked up the clipboard threateningly again. “Lady Schrapnell—”

“She didn’t send him to 1940, did she?” I asked. Badri was of Pakistani descent. He’d be arrested as a Japanese spy.

“No,” she said. “She made him drive her to London to look for some historian who’s gone missing. Which leaves me to run Wardrobe and the net and deal with people who waste my time asking stupid questions.” She crashed the clipboard down. “Now, if you don’t have any more of them, I have a priority fix to calculate.” She whirled back to the console and began pounding fiercely at the keys.

Or perhaps an arch-archangel, one of those beings with enormous wings and hundreds of eyes, “and they were terrible to see.” What were they called? Sarabands?

“I think I’d better go fetch Mr. Dunworthy,” Finch whispered to me. “You’d best stay here.”

I was more than glad to comply. I was beginning to feel the drowsiness that the nurse at Infirmary had questioned me about, and all I wanted to do was sit down and rest. I found a chair on the far side of the net, took a stack of gas masks and stirrup pumps off another one so I could put my feet up on it, and stretched out to wait for Finch and try to remember the name of arch-archangels, the ones “full of eyes round about.” It began with an “S.” Samurai? No, that was Lady Schrapnell. Sylphs? No, those were heavenly sprites, who flitted through the air. The water sprites began with something else. An “N.” Nemesis? No, that was Lady Schrapnell.

What were they called? Hylas had come upon them while he was fetching water from a pond, and they had pulled him into the water with them, twining their white arms about him, tangling him in their trailing auburn hair, drowning him in the dark, deep waters.

I must have dozed off because when I opened my eyes, Mr. Dunworthy was there, and the tech was threatening him with her clipboard.

“It’s out of the question,” she was saying. “I’ve got four fixes to do, eight rendezvouses, and I’ve got to replace a costume one of your historians got wet and ruined.” She flipped violently through the sheets on the clipboard. “The soonest I can fit you in is Friday the seventh at half-past three.”

“The seventh?” Finch gurgled. “That’s next week!”

“It must be today,” Mr. Dunworthy said.

“Today?” she said, raising the clipboard like a weapon. “Today?”

Seraphim. “Full of eyes all around and within, and fire, and out of the fire went forth lightning.”

“It won’t require calculating new time coordinates,” Mr. Dunworthy said. “We’re using the ones Kindle came through from. And we can use the drop you’ve got set up at Muchings End.” He looked round at the lab. “Where’s the tech in charge of Wardrobe?”

“In 1932,” she said. “Sketching choir robes. On a priority jump for Lady Schrapnell to see whether their surplices were linen or cotton. Which means I’m in charge of Wardrobe. And the net. And everything else around here.” She flipped the pages back down to their original position and set it down on the net console. “The whole thing’s out of the question. Even if I could fit you in, he can’t go like that, and, besides, he’d need to be prepped on Victorian history and customs.”

“Ned’s not going to tea with the Queen,” Mr. Dunworthy said. “His assignment will only bring him into limited contact with the contemps, if any. He won’t need a course in Victoriana for that.”

The seraphim reached for her clipboard.

Finch ducked.

“He’s Twentieth Century,” she said. “That means he’s out of his area. I can’t authorize his going without his being prepped.”

“Fine,” Mr. Dunworthy said. He turned to me. “Darwin, Disraeli, the Indian question, Alice in Wonderland, Little Nell, Turner, Tennyson, Three Men in a Boat, crinolines, croquet—”

“Penwipers,” I said.

“Penwipers, crocheted antimacassars, hair wreaths, Prince Albert, Flush, frock coats, sexual repression, Ruskin, Fagin, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, George Bernard Shaw, Gladstone, Galsworthy, Gothic Revival, Gilbert and Sullivan, lawn tennis, and parasols. There,” he said to the seraphim. “He’s been prepped.”

“Nineteenth Century’s required course is three semesters of political history, two—”

“Finch,” Mr. Dunworthy said. “Go over to Jesus and fetch a headrig and tapes. Ned can do high-speed subliminals while you,” he turned back to the seraphim, “get him dressed and set up the jump. He’ll need summer clothes, white flannels, linen shirt, boating blazer. For luggage, he’ll need . . .”

“Luggage!” the seraphim said, sprouting eyes. “I don’t have time to collect luggage! I have nineteen jumps—”

“Fine,” Mr. Dunworthy said. “We’ll take care of the luggage. Finch, go over to Jesus and fetch some Victorian luggage. And did you contact Chiswick?”

“No, sir. He wasn’t there, sir. I left a message.”

He left, colliding with a tall, thin young black man on his way out. The black man had a sheaf of papers, and he looked no older than eighteen, and I assumed he was one of the pickets from outside and held out my hand for a leaflet, but he went up to Mr. Dunworthy and said nervously, “Mr. Dunworthy? I’m T.J. Lewis. From Time Travel. You were looking for Mr. Chiswick?”

“Yes,” Mr. Dunworthy said. “Where is he?”

“In Cambridge, sir,” he said.

“In Cambridge? What the devil’s he doing over there?”

“Ap-applying for a job, sir,” he stammered. “H-he quit, sir.”

“When?”

“Just now. He said he couldn’t stand working for Lady Schrapnell another minute, sir.”

“Well,” Mr. Dunworthy said. He took his spectacles off and peered at them. “Well. All right, then. Mr. Lewis, is it?”

“T.J., sir.”

“T.J., would you go tell the assistant head—what’s his name? Ranniford—that I need to speak with him. It’s urgent.”

T.J. looked unhappy.

“Don’t tell me he’s quit as well?”

“No, sir. He’s in 1655, looking at roof slates.”

“Of course,” Mr. Dunworthy said disgustedly. “Well, then, whoever else is in charge over there.”

T.J. looked even unhappier. “Uh, that would be me, sir.”

“You?” Mr. Dunworthy said in surprise. “But you’re only an undergraduate. You can’t tell me you’re the only person over there.”

“Yes, sir,” T.J. said. “Lady Schrapnell came and took eve

ryone else. She would have taken me, but the first two-thirds of Twentieth Century and all of Nineteenth are a ten for blacks and therefore off-limits.”

“I’m surprised that stopped her,” Mr. Dunworthy said.

“It didn’t,” he said. “She wanted to dress me up as a Moor and send me to 1395 to check on the construction of the steeple. It was her idea that they’d assume I was a prisoner brought back from the Crusades.”

“The Crusades ended in 1272,” Mr. Dunworthy said.

“I know, sir. I pointed that out, also the fact that the entire past is a ten for blacks.” He grinned. “It’s the first time my having black skin has been an actual advantage.”

“Yes, well, we’ll see about that,” Mr. Dunworthy said. “Have you ever heard of Ensign John Klepperman?”

“No, sir.”

“World War II. Battle of Midway. The entire bridge of his ship was killed and he had to take over as captain. That’s what wars and disasters do, put people in charge of things they’d never ordinarily be in charge of. Like Time Travel. In other words, this is your big chance, Lewis. I take it you’re majoring in temporal physics?”

“No, sir. Comp science, sir.”

Mr. Dunworthy sighed. “Ah, well, Ensign Klepperman had never fired a torpedo either. He sank two destroyers and a cruiser. Your first assignment is to tell me what would happen if a parachronistic incongruity had occurred, what indications we would have of it. And don’t tell me it couldn’t happen.”

“Para-chron-istic incon-gruity,” T.J. said, writing it on the top of the papers he was holding. “When do you need this, sir?”

“Yesterday,” Mr. Dunworthy said, handing him the bibliography from the Bodleian.

T.J. looked bewildered. “You want me to go back in time and—”

“I am not setting up another drop,” Warder cut in.

Mr. Dunworthy shook his head tiredly. “I meant I need the information as soon as possible,” he said to T.J.

Passage

Passage Bellwether

Bellwether Blackout

Blackout Doomsday Book

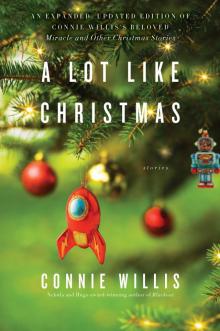

Doomsday Book A Lot Like Christmas: Stories

A Lot Like Christmas: Stories Water Witch

Water Witch To Say Nothing of the Dog

To Say Nothing of the Dog Fire Watch

Fire Watch The Winds of Marble Arch and Other Stories

The Winds of Marble Arch and Other Stories Uncharted Territory

Uncharted Territory All Clear

All Clear Crosstalk

Crosstalk Lincoln's Dreams

Lincoln's Dreams Miracle and Other Christmas Stories

Miracle and Other Christmas Stories Time is the Fire

Time is the Fire Blackout ac-1

Blackout ac-1 Dooms Day Book

Dooms Day Book Jack

Jack The Doomsday Book

The Doomsday Book Terra Incognita

Terra Incognita The Best of Connie Willis

The Best of Connie Willis Cibola

Cibola Schwarzschild Radius

Schwarzschild Radius Even the Queen

Even the Queen The Last of the Winnebagos

The Last of the Winnebagos Spice Pogrom

Spice Pogrom Oxford Time Travel 1 - Blackout

Oxford Time Travel 1 - Blackout At The Rialto

At The Rialto A Lot Like Christmas

A Lot Like Christmas