- Home

- Connie Willis

Lincoln's Dreams Page 2

Lincoln's Dreams Read online

Page 2

“If this Pentagon job is so great, how come the guy’s a patient of yours?” I’d said instead.

“He has a sleep disorder.”

“Well, I sleep great nights,” I’d said. “Tell him thanks but no thanks.” I wondered if he was calling now with another job offer. Broun had said Richard wouldn’t tell him what he wanted to talk to me about, which meant it probably was, and I was in no shape to listen to it.

I took a hot shower instead and then tried for a nap, but I found myself still thinking about Richard and decided to call him and get it over with. I went back into Broun’s study to use the phone. I thought maybe the girlfriend Broun had talked to would answer, but she didn’t. Richard did, and he didn’t have any job offers.

“Where in the hell have you been? I tried to call you,” he said.

“I was in West Virginia,” I said. “Seeing a man about a horse. What did you want to talk to me about?”

“Nothing. It’s too late, anyway. Broun said he’d have you call me,” he said almost accusingly. Why was I constantly finding myself in conversations I couldn’t make heads or tails of?

“I’m sorry I didn’t call. I just got home. But listen, whatever it was, we can talk about it tonight at the reception.”

There was dead silence on the other end.

“You are coming, aren’t you?” I said. “Broun’s really anxious to talk to you about Lincoln’s dreams.”

“I can’t come,” he said. “It’s out of the question. I have a patient I—”

“We’re closer to the Sleep Institute than your apartment is. You can give the Institute Broun’s number, and they can call you here if there’s an emergency. I’d really like to see you, and I want to meet this new girlfriend of yours.”

Another dead silence. He said finally, “I don’t think Annie should—”

“Come with you? Of course she should. I’ll take good care of her while you talk to Broun. I’ll tell her all about your wild undergraduate days at Duke.”

“No. Tell your boss I’m sorry, but I don’t have anything to tell him about Lincoln’s dreams that he’d want to hear.”

Somewhere along in there I started to ache all over. “Then tell him that. Look,” I said, “you don’t have to come for the whole thing. The reception starts at eight. You can talk to Broun and still have this Annie person home in bed by nine watching her rapid eye movements or whatever it is you psychiatrists do. Please. If you don’t come, Broun’ll send me to Indiana in this blizzard to look up nightmares Lincoln had as a kid. Come on, for me, your old roommate.”

“I can’t stay after nine.”

“No problem,” I said. I gave him Broun’s address and hung up before he could say no, and then just sat there in front of the fire. Broun’s cat jumped on my lap and I sat there petting it, thinking I should get up and go lie down.

Broun woke me up. “How long was I asleep?” I said, rubbing my hands over my face to try and wake up. However long it had been, the aches were worse than ever.

“It’s six-thirty,” Broun said. He had changed into a dinner jacket with a pleated shirt and string tie. He still hadn’t shaved. Maybe he was trying to grow a beard. If he was, it was a terrible idea. The grayish black stubble seemed to take all the color out of his face. He looked sharp and disreputable, like an unscrupulous horsetrader. “I wouldn’t have wakened you, but I wanted you to take a look at this.” He thrust a sheaf of typewritten pages into my hand.

“What’s this?” I said. “Willie Lincoln?”

He poked at the fire, which had died down to almost nothing while I was asleep. “It’s that first scene, the one I was worried about. I just couldn’t see Ben signing up for no reason at all, so I rewrote it.”

“Do McLaws and Herndon know about this?” Broun’s cat jumped off my lap and started batting at the poker.

“I’m calling it in to them tomorrow, but I wanted you to look at it first. Ben had to have some motivation for enlisting.”

“Why? What about later in the book when he falls in love with Nelly? He doesn’t have any motivation for that. She gives him one spoonful of laudanum, and bang, he’s ready to do anything for her.”

The cat wrapped a paw firmly around the poker, but Broun didn’t notice. He stared into the fire. “It was the war. People did things like that during the war, fell in love, sacrificed themselves—”

“Enlisted,” I said. “Most of the recruits in the Civil War didn’t have any motivation for enlisting. There was a war, and they signed up on one side of it or the other.” I tried to hand the scene back to him. “I don’t think you need a new scene.”

He put the poker back in the stand. The cat lay down in front of it, tail switching. “Anyway, I’d like you to read it,” Broun said. “Did you call your roommate?”

“Yes.”

“Is he coming.”

“I don’t know. I think so.”

“Good. Good. Now we’ll run this dream thing to ground. Be sure and tell me when he gets here.” He started out the door. “I’m going to go check on the caterers.”

“Hadn’t you better shave?”

“Shave?” he said, sounding horrified. “Can’t you see I’m growing muttonchop whiskers?” He struck a pose with his hands in his lapels. “Like Lincoln’s.”

“You don’t look like Lincoln,” I said, grinning. “You look like Grant after a binge.”

“I could say the same thing about you, son,” he said, and went downstairs to talk to the caterers.

I tried to read the new scene, wishing I had the time to run a few dreams of my own to ground. I felt tireder than I had before the nap. I couldn’t even get my eyes to focus on Broun’s typing. The reporters would be here any minute, and then I would stand propped up against a wall for endless hours telling people why Broun’s book wasn’t ready, and then tomorrow I would go out to Arlington and poke around in the snow, looking for Willie Lincoln’s grave.

If I could find out where he was buried, I might not have to spend tomorrow out wiping snow off old tombstones. I put down the rewritten scene and looked for Sandburg’s War Years.

Broun has never believed in libraries—he keeps books all over the house, and whenever he finishes with one, he sticks it into the handiest bookcase. I offered once to organize the books, and he said, “I know where they all are.” He might know, but I didn’t, so I had organized them for myself—Grant and the western campaign in the big upstairs dining room, Lee in the solarium, Lincoln in the study. It didn’t do much good. Broun still left books wherever he finished with them, but it was better than nothing. I had at least an even chance of finding what I needed. Usually. Not this time, though.

Sandburg’s War Years wasn’t where I’d put it, and neither was Oates. It took me almost an hour to find them, Oates in the upstairs bathroom, Sandburg down in the solarium underneath one of Broun’s African violets. Before I even got upstairs with them, a young woman from People snowed up and tried to pump me about Broun’s new book.

“What’s it about?” she asked.

“Antietam,” I said. “It’s in the press release.”

“Not that one. The new one he’s starting.”

“Your guess is as good as mine,” I said, and turned her over to Broun and went back into the study with the books I’d found and looked up Willie Lincoln. He had died in 1862, when he was eleven years old. They had had a reception downstairs in the White House while he lay dying upstairs. And probably people had kept ringing the doorbell, I thought, when the doorbell rang.

It was more reporters, and then it was somebody from the caterer’s and then more reporters, and I began to think Richard wasn’t coming after all, but the next time the doorbell rang it was Richard. With Annie.

“We can’t stay very long,” Richard said before he even got in the door. He looked tired and strung out, which wasn’t much of an endorsement for the Sleep Institute. I wondered if the way he looked had anything to do with his having called me when I was in West Virginia.

“I’m glad you both could come,” I said, turning to look at Annie. “I’m Jeff Johnston. I used to room with this guy back Before he became a hotshot psychiatrist.”

“I’m glad to meet you, Jeff,” she said gravely.

She was not at all what I’d expected. Richard had dated mostly hot little nurses when he was in med school, and Washington’s Women on the Way Up since he started working at the Institute. He had never so much as glanced at anyone like Annie. She was little, with short blonde hair and bluish gray eyes. She was wearing a heavy gray coat and low-heeled shoes and looked about eighteen.

“The party’s upstairs,” I said. “It’s kind of a zoo, but…”

“We don’t have much time,” Richard said, but he didn’t look at his watch. He looked at Annie, as if she were the one in a hurry. She didn’t look worried at all.

“How about if I bring Broun down here?” I said, not at all sure I could get him away from the reporters. “You can wait in the solarium.” I motioned them in.

It was, like every other room in the house, really a room for Broun to misplace books in, even though it had been intended for tropical plants. It had greenhouse glass windows and a neater that kept it twenty degrees hotter than the rest of the house. Broun had stuck a token row of African violets on a table in front of the windows and added an antique horsehair loveseat and a couple of chairs, but the rest of the room was filled with books. “Let me take your coats,” I said.

“No,” Richard said with an anxious glance at Annie. “No. We won’t be here that long.”

I tore up the stairs and got Broun. The caterers had just set out the buffet supper, so he wouldn’t even be missed. I told Broun that Richard was here but couldn’t stay and herded him toward the stairs, but the reporter from People latched on to him, and it was a good five minutes before he could get away from her.

They were still there, but just barely. Richard was at the door of the solarium, saying, “It’s almost nine. I think …”

“Glad to meet you, Dr. Madison. So you’re Jeff’s old roommate,” Broun said, putting himself between Richard and the front door. “And you must be Annie. I talked to you on the phone.”

“Yes,” she said. “I’ve been wanting to meet you, Mr. Brou—”

“I understand you wanted to talk to me about Abraham Lincoln,” Richard said, cutting across her words before she even got Broun’s name out.

“I do,” Broun said. “I appreciate your coming. I’ve been doing some research on Lincoln. He had some mighty strange dreams,” he smiled at Annie, “and since you told me Dr. Madison here tells people what their dreams mean, I thought maybe he could tell me about Lincoln’s dreams.” He turned back to Richard. “Have you had supper? There’s a wonderful buffet upstairs if the reporters haven’t eaten it all. Lobster and ham and some wonderful shrimp doodads that…”

“I don’t have very much time,” Richard said, looking at Annie. “I told Jeff on the phone I didn’t think I could help you. You can’t analyze somebody’s dreams just by hearing a secondhand account of them. You have to know all about the person.”

“Which Broun does,” I said.

“I mostly need some information on what the modern view of dreams is,” Broun said, taking hold of Richard’s arm. “I promise I’ll only take a few minutes of your time. We can all go up to my study. We’ll grab something to eat on the way and—”

“I don’t think …” Richard said, with another anxious glance at Annie.

“You’re absolutely right,” Broun said, his hand clamped firmly on Richard’s arm. “Why should your young lady have to be bored by a lot of dry history when she can go to a party instead? Jeff, you’ll keep her company, won’t you? Get her some of those shrimp doodads and some champagne?”

Richard looked at Annie as it he expected her to object, but she didn’t say anything, and I thought he looked relieved.

“Jeff’ll take good care of her,” Broun said heartily, like a man trying to make a deal. “Won’t you, Jeff?”

“I’ll take care of her,” I said, looking at her. “I promise.”

“The dream I’m having trouble with is one Lincoln had two weeks before his assassination,” Broun said, leading Richard firmly up the stairs to his study. “He dreamed he woke up in the White House and heard somebody crying. When he went downstairs …” They disappeared into the roar of noise and people at the top of the stairs. I turned and looked at Annie. She was standing looking up after them.

“Would you like to go up to the party?” I said. “Broun’ll be upset if you don’t have some of the shrimp doodads.”

She smiled and shook her head. “I don’t think Richard will be that long.”

“Yeah, he didn’t seem all that enthusiastic about the prospect of analyzing Lincoln’s dreams.” I led the way back into the solarium. “He kept talking about having to leave. Is one of his patients giving him a rough time?”

She went over to the windows and looked out. “Yes,” she said. “Richard told me you’re a historian.”

“Did he also tell you he thinks I’m crazy for spending my life looking up obscure facts that don’t matter to anybody?”

“No,” she said, still watching the rain turn into sleet. “That’s a term he reserves for me these days.” She turned and looked at me. “I’m a patient of his. I have a sleep disorder.”

“Oh,” I said. “Can I take your coat?” I said, to be saying something. “Broun keeps this room like an oven.”

She gave it to me, and I went and hung it in the hall closet, trying to make sense of what she’d just told me. Richard hadn’t contradicted me when I’d called her his girlfriend, and Broun had told me she answered the phone at Richard’s apartment, but if she was his patient, what was he doing living with her?

When I came back into the solarium, she was looking at Broun’s African violets. I went over to the windows and looked out, trying to think of something to talk about. I could hardly ask her if she was sleeping with Richard or if her sleep disorder had anything to do with him.

“I’ve got to go out to Arlington National Cemetery in this mess tomorrow,” I said. “I’ve got to try and find where Willie Lincoln was buried, for Broun. Willie was Abraham Lincoln’s little boy. He died during the war.”

“Do you do all of Broun’s Civil War research for him?” Annie said, picking up one of the African violets.

“Most of the legwork. You know, when Broun first hired me, he would hardly let me do any of his research. It took me almost a year to talk him into letting me run his errands for him, and now I wish I hadn’t done such a good job. It looks like it’s turning into snow out there.”

She put the flowerpot back down on the table and looked up at me. “Tell me about the Civil War,” she said.

“What do you want to know?” I asked. I wished suddenly that I had had that nap so I could give my full wits to this conversation, tell her stories about the war that would get that somehow sad expression out of her blue-gray eyes. “I’m an expert on Antietam. Bloodiest single day of the Civil War. Possibly the most important day, too, though Broun will argue with that. General Lee needed a victory so England would recognize the Confederacy, and so he invaded Maryland, only it didn’t work. He had to retreat back to Virginia and …”

I stopped. I was putting myself to sleep, and God only knew what I was doing to Annie, who had probably never heard of Antietam. “How about Robert E. Lee? And his horse. I know just about everything there is to know about his damned horse.”

She brushed her short hair back from her face and smiled. “Tell me about the soldiers,” she said.

“The soldiers, huh? Well, they were farm boys mostly, uneducated. And they were young. The average age of the Civil War soldier was twenty-three.”

“I’m twenty-three,” she said.

“I don’t think you’d have had too much to worry about. They didn’t draft women in the Civil War,” I said, “though they might have had to if the war had gone on much longer. The C

onfederacy was down to old men and thirteen-year-old boys. If you’re interested in soldiers, there are a whole slew of them buried out at Arlington,” I said. “How would you like to go out there with me tomorrow?”

She picked up another of the potted violets and traced her finger along the leaves. “To Arlington?” she said.

Richard and I had roomed together at Duke for four years. I had never even looked at one of his girls, and tonight I had told him I would take care of? her for him. “Arlington’s a great place to visit,” I said, as if I hadn’t spent the last three days and nights living on No-Doz and coffee and wanting nothing more than to get back to Broun’s and sleep straight through till spring, as if she weren’t living with my old roommate. “There are a lot of famous people buried there, and the house is open to the public.”

“The house?” she said, bending over another one of the violets.

“Robert E. Lee’s house,” I said. “It was his plantation until the war. Then the Union occupied it. They buried Union soldiers in the front lawn to make sure he never got it back, and he never did. They turned it into a national cemetery in 1864. I’ve done a lot of research on Robert E. Lee lately.”

She was looking at me. And she had put her hand in the flowerpot. “Did he have a cat?” she said.

I turned and looked behind me at the door, thinking Broun’s Siamese had come down here to get away from the party, but it wasn’t there. “What?” I said, looking at her hand.

“Did Robert E. Lee have a cat? When he lived at Arlington?”

I was too tired, that was all. If I could just have gotten a nap instead of looking up Willie Lincoln and talking to reporters, I would have been able to take all this in—me asking her out when she was living with Richard, her asking me if Lee had a cat while she scrabbled in the dirt of the flowerpot as if she were trying to dig a grave.

“What kind of cat?” I said.

She had pulled the violet up by its roots and was holding it tightly in her hand. “I don’t know. A yellow cat. With darker stripes. It was there, in the dream.”

Passage

Passage Bellwether

Bellwether Blackout

Blackout Doomsday Book

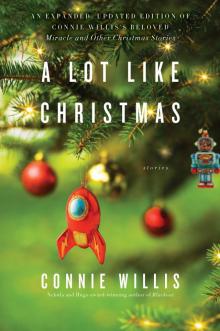

Doomsday Book A Lot Like Christmas: Stories

A Lot Like Christmas: Stories Water Witch

Water Witch To Say Nothing of the Dog

To Say Nothing of the Dog Fire Watch

Fire Watch The Winds of Marble Arch and Other Stories

The Winds of Marble Arch and Other Stories Uncharted Territory

Uncharted Territory All Clear

All Clear Crosstalk

Crosstalk Lincoln's Dreams

Lincoln's Dreams Miracle and Other Christmas Stories

Miracle and Other Christmas Stories Time is the Fire

Time is the Fire Blackout ac-1

Blackout ac-1 Dooms Day Book

Dooms Day Book Jack

Jack The Doomsday Book

The Doomsday Book Terra Incognita

Terra Incognita The Best of Connie Willis

The Best of Connie Willis Cibola

Cibola Schwarzschild Radius

Schwarzschild Radius Even the Queen

Even the Queen The Last of the Winnebagos

The Last of the Winnebagos Spice Pogrom

Spice Pogrom Oxford Time Travel 1 - Blackout

Oxford Time Travel 1 - Blackout At The Rialto

At The Rialto A Lot Like Christmas

A Lot Like Christmas