- Home

- Connie Willis

To Say Nothing of the Dog Page 17

To Say Nothing of the Dog Read online

Page 17

“I say, have you found it yet?” Terence called out from the direction of the riverbank.

I sat up, dusting off my elbows, and looked at Cyril. “Don’t you say a word.” I stood up.

Terence appeared, carrying the tin of peaches. “ There you are,” he said. “Any luck?”

“None at all,” I said. I walked rapidly back to the luggage. “I mean, I haven’t finished looking through everything.”

I jammed the lid on the basket and opened the satchel, hoping fervently it didn’t contain any surprises. It didn’t. It contained a pair of lace-up boots that couldn’t have been more than a size five, a large spotted handkerchief, three fish forks, a large filigreed silver ladle, and a pair of escargot tongs. “Would this work?” I said, holding them up.

Terence was rummaging through the hamper. “I doubt . . . here it is,” he said, holding up the scimitar-looking object with the red handle. “Oh, you’ve brought Stilton. Excellent.” He went off, clutching the tin-opener and the cheese, and I went back over to the edge of the clearing.

There was no sign of the cat. “Here, Princess Arjumand,” I said, lifting up leaves to look under the bushes. “Here, girl.”

Cyril nosed at a bush, and a bird flew up.

“Come, cat,” I said. “Heel.”

“Ned! Cyril!” Terence called, and I dropped the branch with a rustle. “The kettle’s boiling!” He appeared, holding the opened tin of peaches. “What’s keeping you?”

“I thought I’d just tidy up a bit,” I said, sticking the escargot tongs in one of the boots, “get everything packed so we can make an early start.”

“You can do it after your dessert,” he said, taking me by the arm. “Come along now.”

He led us back to the campfire, Cyril looking warily from side to side, where Professor Peddick was pouring out tea into tin cups.

“Dum licet inter nos igitur laetemur amantes,” he said, handing me a cup. “The perfect end to a perfect day.”

Perfect. I’d failed to return the cat, kept Terence from meeting Maud, made it possible for him to get to Iffley to see Tossie, and who knew what else?

There was no use crying over spilt milk, even if that was an unfortunate metaphor, because it couldn’t be put back in the bottle, no matter how hard one tried, and what exactly would be a good metaphor? Opening Pandora’s box? Letting the cat out of the bag?

Whatever, there was no use crying over it, or thinking about what might have been. I had to get Princess Arjumand back to Muchings End as soon as possible, and before any more damage was done.

Verity had said to keep Terence away from Tossie, but she hadn’t known about the cat. I had to get it back to the site of its disappearance immediately. And the quickest way to do that was to tell Terence I’d found it. He’d be overjoyed. He’d insist on starting to Muchings End immediately.

But I didn’t want to create anymore consequences, and Tossie might be so grateful to him for returning Princess Arjumand she’d fall in love with him instead of Mr. C. Or he might start wondering how the cat had got so far from home and insist on setting off after its kidnapper the way he had after the boat and end up going over a weir in the dark and drowning. Or drowning the cat. Or causing the Boer War.

I’d better keep the cat hidden until we got to Muchings End. If I could get it back in the basket. If I could find it.

“If we were to find Princess Arjumand,” I said, I hoped casually, “how would one go about catching her?”

“I shouldn’t think she’d need catching,” Terence said. “I should think she’d leap gratefully into our arms as soon as she saw us. She’s not used to fending for herself. From what Toss—Miss Mering told me, she’s had rather a sheltered life.”

“But suppose she didn’t. Would she come if you called her by name?”

Terence and the professor both stared at me in disbelief. “It’s a cat,” Terence said.

“So how would one set about catching her if she were frightened and wouldn’t come? Would one use a trap or—”

“I should think a bit of food would do it. She’s bound to be hungry,” Terence said, staring out at the river. “Do you suppose she’s looking at the river as I am, ‘’mid the cool airs of Evening, as she trails her robes of gold through the dim halls of Night’?”

“Who?” I said, scanning the riverbank. “Princess Arjumand?”

“No,” Terence said irritably. “Miss Mering. Do you suppose she’s looking at this same sunset? And does she know, as I do, that we are fated to be together, like Lancelot and Guinevere?”

Another bad end, but nothing compared to the one we were all going to come to if I didn’t find that cat and get it back to Muchings End.

I stood up and began picking up plates. “We’d best clear things away and then get to bed so we can make an early start tomorrow.”

“Ned’s right,” Terence said to Professor Peddick, pulling himself reluctantly away from the river. “We’ll need to start early for Oxford.”

“Is Oxford necessary, do you think?” I said. “Professor Peddick could go with us down to Muchings End, and we could take him back later.”

Terence was looking at me disbelievingly.

“It would save two hours at the least, and there must be any number of historical sights along the river Professor Peddick could study,” I said, improvising. “Ruins and tombs and . . . Runnymede.” I turned to Professor Peddick. “I suppose it was blind forces that led to the signing of the Magna Carta.”

“Blind forces?” Professor Peddick said. “It was character that led to the Magna Carta. King John’s ruthlessness, the Pope’s slowness in acting, Archbishop Langton’s insistence on habeas corpus and the rule of law. Forces! I’d like to see Overforce explain the Magna Carta in terms of blind forces!” He drained his teacup and set it down decisively. “We must go to Runnymede!”

“But what about your sister and your niece?” Terence said.

“My scout can provide anything they need, and Maudie’s a resourceful girl. That was King John’s mistake, you know, going to Oxford. He should have stayed in London. The entire course of history might have been different. We won’t make that mistake,” he said, and picked up his fishing pole. “We shall go to Runnymede. Only thing to do.”

“But your sister and your niece won’t know where you’ve gone,” Terence said, frowning questioningly at me.

“He can send a telegram from Abingdon,” I said.

“Yes, a telegram,” Professor Peddick said and hobbled off toward the river.

Terence looked worriedly after him. “You don’t think he’ll slow us down?”

“Nonsense,” I said. “Runnymede’s down near Windsor. I can take him down in the boat while you’re at Muchings End with Miss Mering. We could be there by midday. You’d have time to wash up so you can look your best. We could stop at the Barley Mow,” I said, pulling the name of an inn out of Three Men in a Boat, “and you could have your trousers pressed and your shoes shined.”

And I can sneak out while you’re shaving and return the cat to Muchings End, I thought. If I can find the cat.

Terence still looked unconvinced. “It would save time, I suppose,” he said.

“Then it’s settled,” I said, scooping up the cloth and stuffing it into the hamper. “You wash the dishes and I’ll make up the beds.”

He nodded. “There’s only room for two of us in the boat. I’ll sleep by the fire.”

“No,” I said. “I will,” and went to get the rugs.

I spread all but two in the bottom of the boat and took the others into the clearing.

“Shouldn’t you put them near the fire?” Terence said, piling dishes up.

“No, my physician said I shouldn’t sleep near smoke,” I said.

While Terence rinsed the dishes, standing ankle-deep in the river with his trousers rolled up, I stole a lantern and a rope, wishing Professor Peddick had brought along a fishing net.

I should have asked Terence what sort of food

cats ate. Some of the Stilton was left. Did cats like cheese? No, that was mice. Mice liked cheese. And cats liked mice. I doubted if we had any mice.

Milk. They were supposed to like milk. The woman running the coconut shy at the Harvest Fete had been complaining about a cat getting into the milk left on her doorstep. “Clawed the cap straight off,” she’d said. “Impudent creature.”

We hadn’t any milk, but there was a bit of cream left in the bottle. I pocketed it, a saucer, a tin of peas and one of potted meat, a heel of bread, and the tin-opener, and hid them in the clearing, and then went back to the campfire.

Terence was digging in the boxes. “Where has that lantern got to?” he said. “I know there were two in here.” He looked up at the sky. “It looks like rain. Perhaps you’d better sleep in the boat. It’ll be a bit crowded, but we can manage.”

“No!” I said. “My physician said river vapors were bad for my lungs,” a pathetic reason since I had just had my physician recommending a trip on the river for my health. “She said I should sleep inland.”

“Who?” Terence said, and I remembered too late that women hadn’t been physicians in Victorian England. Or solicitors or prime ministers.

“My physician. James Dunworthy. He said I should sleep inland and away from others.”

Terence straightened up, holding the lantern by its handle. “I know Dawson packed two. I watched him. I’ve no idea where it got to.”

He lit the lantern, removing the glass cover, striking a match, and adjusting the wick. I watched him carefully.

Professor Peddick came up, carrying the kettle with his two fish in it. “I must notify Professor Edelswein of my discovery. The Ugubio fluviatilis albinus was thought to be extinct in the Thames,” he said, peering at it in the near-darkness. “A beautiful specimen.” He set it down on the hamper and got out his pipe again.

“Shouldn’t we be going to bed?” I said. “Early start and all that?”

“Quite right,” he said, opening his tobacco pouch. “A good night’s sleep can be critical. The Greeks at Salamis had had a good night’s sleep the night before.” He filled his pipe and tamped the tobacco down with his thumb. Terence took out his pipe. “The Persians, on the other hand, had spent the night at sea, positioning their ships to prevent the Greeks from escaping.” He lit his pipe and sucked on it, trying to light it.

“Exactly, and the Persians were routed,” I said. “We don’t want that to happen to us. So” I stood up. “To bed.”

“The Saxons, too, at the Battle of Hastings,” Professor Peddick said, handing his tobacco pouch to Terence. They both sat down. “William the Conqueror’s men were rested and ready for battle, while the Saxons had been on the march for eleven days. If Harold had waited and allowed his men to rest, he would have won the Battle of Hastings, and the whole course of history might have been changed.”

And if I didn’t get the cat back, ditto.

“Well, we don’t want to lose any battles on the morrow,” I said, trying again, “so we’d best get to bed.”

“Individual action,” Professor Peddick said, puffing on his pipe. “That’s what lost the Battle of Hastings. The Saxons had the advantage, you know. They were drawn up on a ridge. Being on a defended height is the greatest military advantage an army can have. Look at Wellington’s army at Waterloo. And the battle of Fredericksburg in the American Civil War. The Union army lost twelve thousand men at Fredericksburg, marching across an open plain to a defended height. And England was a richer country, fighting on their own home ground. If economic forces are what drives history, the Saxons should have won. But it wasn’t forces that won the Battle of Hastings. It was character. William the Conqueror changed the course of the battle at at least two critical points. The first came when William was unhorsed during a charge.”

Cyril lay down and began to snore.

“If William had not gotten immediately to his feet and pushed back his helmet so that his men could see that he was alive, the battle would have been lost. How does Overforce fit that into his theory of natural forces? He can’t! Because history is character, as is proved by the second crisis point of the battle.”

It was a full hour before they knocked the tobacco out of their pipes and started down to the boat. Halfway there, Terence turned and came back. “Perhaps you’d better take the lantern,” he said, holding it out to me, “since you’re sleeping on shore.”

“I’ll be perfectly all right,” I said. “Good night.”

“Good night,” he said, starting down to the boat again. “‘Night is the time for rest.’” He waved to me. “‘How sweet when labors close, To gather round an aching breast the curtain of repose.’”

Yes, well, it would be, but I had a cat to find first. I went back to the clearing to wait for everyone to go to sleep, trying not to think about how every moment the cat was loose the number of consequences multiplied exponentially.

It might have been eaten by a wolf. Did Victorian England have wolves? Or found by an old woman in a cottage and taken in. Or picked up by a passing boat.

The locks are closed, I told myself, and it’s only a cat. How much of an effect on history can an animal have?

A big one. Look at Alexander the Great’s horse Bucephalus, and “the little gentleman in the black fur coat” who’d killed King William the Third when his horse stepped in the mole’s front door. And Richard the Third standing on the field at Bosworth and shouting, “My kingdom for a horse!” Look at Mrs. O’Leary’s cow. And Dick Whittington’s cat.

I waited half an hour and then cautiously lit the lantern. I took the tins out from their hiding place and pulled the tin-opener out of my pocket. And tried to open them.

It was definitely a tin-opener. Terence had said it was. He’d opened the peaches with it. I poked at the lid with the point of the scimitar and then with the side of it. I poked at it with the other, rounded edge.

There was a space between the two. Perhaps one fit on the outside of the tin as a sort of lever for the other. Or perhaps it went in from the side. Or the bottom. Or perhaps I was holding it the wrong way round, and the scimitar thing was the handle.

That resulted in a hole in the palm of my hand, not exactly the idea. I rummaged through the satchel for a handkerchief to wrap round it.

All right, look at the thing logically. The point of the scimitar had to be the part that went through the tin. And it had to go through the lid. Perhaps there was a specific place in the lid where it fit. I examined the lid for weaknesses. It hadn’t any.

“Why did the Victorians have to make everything so bloody complicated?” I said and saw a flicker of light at the near edge of the clearing.

“Princess Arjumand?” I said softly, holding up the lantern, and I had been right about one thing. Cats’ eyes did glow in the dark. Two were shining yellowly at me from the bushes.

“Here, cat,” I said, holding out the heel of bread and making “tsk”ing noises. “I’ve got some food for you. Come here.”

The glowing eyes blinked and then disappeared. I stuck the bread in my pocket and started carefully for the edge of the clearing. “Here, cat. I’ll take you home. You want to go home, don’t you?”

Silence. Well, not exactly silence. Frogs croaked, leaves rustled, and the Thames made a peculiar gurgling sound as it flowed past. But no cat sounds. And what sounds did cats make? Since all the cats I’d ever seen had been asleep, I wasn’t sure. Meowing sounds. Cats meowed.

“Meow,” I said, lifting branches to look under the bushes. “Come here, cat. You wouldn’t want to destroy the space-time continuum, would you? Meow. Meow.”

There the eyes were again, past that thicket. I set off through it, dropping bread crumbs as I went. “Meow?” I said, swinging the lantern slowly from side to side. “Princess Arjumand?” and nearly tripped over Cyril.

He wagged his nether half happily.

“Go back and sleep with your master,” I hissed. “You’ll just get in the way.”

He imme

diately lowered his flat nose to the ground and began snuffling in circles.

“No!” I whispered. “You’re not a bloodhound. You haven’t even got a nose. Go back to the boat.” I pointed toward the river.

He stopped snuffling and looked up at me with bloodshot eyes that could have been a bloodhound’s and an expression that clearly said, “Please.”

“No,” I said firmly. “Cats don’t like dogs.”

He began snuffling again, what passed for his nose earnestly to the ground.

“All right, all right, you can come with me,” I said, since it was obvious he was going to anyway. “But stay with me.”

I went back into the clearing, poured the cream into a bowl, and got the rope and sortie matches. Cyril watched interestedly.

I held the lantern aloft. “‘The game’s afoot, Watson,’” I said, and we set off into the wilderness.

It was very dark, and along with the frogs, river, and leaves were assorted slitherings and rattlings and hoots. The wind picked up, and I sheltered the lantern with my hand, thinking what a wonderful invention the pocket torch was. It gave off a powerful light, and one could point the beam in any direction. The lantern’s light I could only direct by holding it up or down. It did give off a warm, wavering circle of light, but its only function seemed to be to make the area outside said circle as black as pitch.

“Princess Arjumand?” I called at intervals, and “Here, cat,” and “Yoo hoo.” I dropped bread crumbs as I went, and periodically I set the dish of cream down in front of a likely looking bush and waited.

Nothing. No glowing eyes. No meows. The night got darker and damper, as if it might rain.

“Do you see any sign of her, Cyril?” I asked.

We trudged on. The place had looked quite civilized this afternoon, but now it seemed to be all thornbushes and tangled underbrush and sinister clawlike branches. The cat could be anywhere.

There. Down by the river. A flash of white.

“Come on, Cyril,” I whispered and started toward the river.

There it was again, in the midst of some rushes, unmoving. Perhaps she was asleep.

Passage

Passage Bellwether

Bellwether Blackout

Blackout Doomsday Book

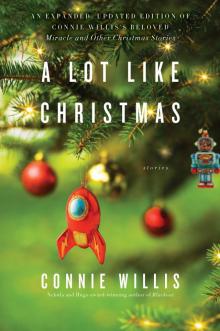

Doomsday Book A Lot Like Christmas: Stories

A Lot Like Christmas: Stories Water Witch

Water Witch To Say Nothing of the Dog

To Say Nothing of the Dog Fire Watch

Fire Watch The Winds of Marble Arch and Other Stories

The Winds of Marble Arch and Other Stories Uncharted Territory

Uncharted Territory All Clear

All Clear Crosstalk

Crosstalk Lincoln's Dreams

Lincoln's Dreams Miracle and Other Christmas Stories

Miracle and Other Christmas Stories Time is the Fire

Time is the Fire Blackout ac-1

Blackout ac-1 Dooms Day Book

Dooms Day Book Jack

Jack The Doomsday Book

The Doomsday Book Terra Incognita

Terra Incognita The Best of Connie Willis

The Best of Connie Willis Cibola

Cibola Schwarzschild Radius

Schwarzschild Radius Even the Queen

Even the Queen The Last of the Winnebagos

The Last of the Winnebagos Spice Pogrom

Spice Pogrom Oxford Time Travel 1 - Blackout

Oxford Time Travel 1 - Blackout At The Rialto

At The Rialto A Lot Like Christmas

A Lot Like Christmas