- Home

- Connie Willis

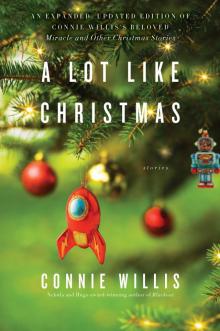

A Lot Like Christmas Page 17

A Lot Like Christmas Read online

Page 17

The Altairi were sitting calmly in the middle of the space between the stores, glaring. A circle of fascinated shoppers had formed a circle around them, and a man in a suit who looked like the manager of the mall was hurrying up, demanding, “What’s going on here?”

“This is wonderful,” Dr. Morthman said. “I knew they’d respond if we just took them enough places.” He turned to me. “You were behind them, Miss Yates. What made them sit down?”

“I don’t know,” I said. “I couldn’t see them from where I was. Did—?”

“Go find Leo,” he ordered. “He’ll have it on tape.”

I wasn’t so sure of that, but I went to look for him. He was just coming out of Victoria’s Secret, carrying a small bright pink bag. “Meg, what happened?” he asked.

“The Altairi sat down,” I said.

“Why?”

“That’s what we’re trying to find out. I take it you weren’t filming them?”

“No, I told you, I had to buy my girlfriend— Jeez, Dr. Morthman will kill me.” He jammed the pink bag into his jeans pocket. “I didn’t think—”

“Well, start filming now,” I said, “and I’ll go see if I can find somebody who caught it on their cell phone camera.” With all these people taking their kids to see Santa, there was bound to be someone with a camera. I started working my way around the circle of staring spectators, keeping away from Dr. Morthman, who was telling the mall manager he needed to cordon off this end of the mall and everyone in it.

“Everyone in it?” the manager gulped.

“Yes, it’s essential. The Altairi are obviously responding to something they saw or heard—”

“Or smelled,” Dr. Wakamura put in.

“And until we know what it was, we can’t allow anyone to leave,” Dr. Morthman said. “It’s the key to our being able to communicate with them.”

“But it’s only two weeks till Christmas,” the mall manager said. “I can’t just shut off—”

“You obviously don’t realize that the fate of the planet may be at stake,” Dr. Morthman said.

I hoped not, especially since no one seemed to have caught the event on film, though they all had their cell phones out and pointed at the Altairi now, in spite of their glares. I looked across the circle, searching for a likely parent or grandparent who might have—

The choir. One of the girls’ parents was bound to have brought a video camera along. I hurried over to the troop of green-robed girls. “Excuse me,” I said to them, “I’m with the Altairi—”

Mistake. The girls instantly began bombarding me with questions.

“Why are they sitting down?”

“Why don’t they talk?”

“Why are they always so mad?”

“Are we going to get to sing? We didn’t get to sing yet.”

“They said we had to stay here. How long? We’re supposed to sing over at Flatirons Mall at six o’clock.”

“Are they going to get inside us and pop out of our stomachs?”

“Did any of your parents bring a video camera?” I tried to shout over their questions, and when that failed, “I need to talk to your choir director.”

“Mr. Ledbetter?”

“Are you his girlfriend?”

“No,” I said, trying to spot someone who looked like a choir director type. “Where is he?”

“Over there,” one of them said, pointing at a tall, skinny man in slacks and a blazer. “Are you going out with Mr. Ledbetter?”

“No,” I said, trying to work my way over to him.

“Why not? He’s really nice.”

“Do you have a boyfriend?”

“No,” I said as I reached him. “Mr. Ledbetter? I’m Meg Yates. I’m with the commission studying the Altairi—”

“You’re just the person I want to talk to, Meg,” he said.

“I’m afraid I can’t tell you how long it’s going to be,” I said. “The girls told me you have another singing engagement at six o’clock.”

“We do, and I’ve got a rehearsal tonight, but that isn’t what I wanted to talk to you about.”

“She doesn’t have a boyfriend, Mr. Ledbetter,” one of the girls said. I took advantage of the interruption to say, “I was wondering if anyone with your choir happened to record what just happened on a video camera or a—”

“Probably. Belinda,” he said to the one who’d told him I didn’t have a boyfriend, “go get your mother.” She took off through the crowd. “Her mom started recording when we left the church. And if she didn’t happen to catch it, Kaneesha’s mom probably did. Or Chelsea’s dad.”

“Oh, thank goodness,” I said. “Our cameraman didn’t get it on film, and we need it to see what triggered their action.”

“What made them sit down, you mean?” he said. “You don’t need a video. I know what it was. The song.”

“What song?” I said. “A choir wasn’t singing when we came in, and anyway, the Altairi have already been exposed to music. They didn’t react to it at all.”

“What kind of music? Those notes from Close Encounters?”

“Yes,” I said defensively, “and Beethoven and Debussy and Charles Ives. A whole assortment of composers.”

“But instrumental music, not vocals, right? I’m talking about a song. One of the Christmas carols on the piped-in Muzak. I saw them sit down. They were definitely—”

“Mr. Ledbetter, you wanted my mom?” Belinda said, dragging over a large woman with a videocam.

“Yes,” he said. “Mrs. Carlson, I need to see the video you shot of the choir today. From when we got to the mall.”

She obligingly found the place and handed it to him. He fast-forwarded a minute. “Oh, good, you got it,” he said, rewound, and held the camera so I could see the little screen. “Watch.”

The screen showed the bus with First Presbyterian Church on its side, the girls getting off, the girls filing into the mall, the girls gathering in front of Crate and Barrel, giggling and chattering, though the sound was too low to hear what they were saying. “Can you turn the volume up?” Mr. Ledbetter said to Mrs. Carlson, and she pushed a button.

The voices of the girls came on: “Mr. Ledbetter, can we go to the food court afterward for a pretzel?”

“Mr. Ledbetter, I don’t want to stand next to Heidi.”

“Mr. Ledbetter, I left my lip gloss on the bus.”

“Mr. Ledbetter—”

The Altairi aren’t going to be on this, I thought. Wait—there, past the green-robed girls, were Dr. Morthman and Leo with his video camera, and then the Altairi. They were just glimpses, though, not a clear view. “I’m afraid—” I said.

“Shh,” Mr. Ledbetter said, pushing down on the volume button again. “Listen.”

He had cranked the volume all the way up. I could hear Reverend Thresher saying, “Look at that! It’s absolutely disgusting!”

“Can you hear the Muzak on the tape, Meg?” Mr. Ledbetter asked. “Sort of,” I said. “What is that?”

“ ‘Joy to the World,’ ” he said, holding it so I could see. Mrs. Carlson must have moved to get a better shot of the Altairi, because there was no one blocking the view of them as they followed Dr. Morthman. I tried to see if they were glaring at anything in particular—the strollers or the Christmas decorations or the Victoria’s Secret mannequins or the sign for the restrooms—but if they were, I couldn’t tell.

“This way,” Dr. Morthman said on the tape, “I want them to see Santa Claus.”

“Okay, it’s right about here,” Mr. Ledbetter said. “Listen.”

“ ‘While shepherds watched…’ ” the Muzak choir sang tinnily.

I could hear Reverend Thresher saying, “Blasphemous!” and one of the girls asking, “Mr. Ledbetter, after we sing can we go to McDonald’s?” and the Altairi abruptly collapsed onto the floor with a floomphing motion, like a crinolined Scarlett O’Hara sitting down suddenly. “Did you hear what they were singing?” Mr. Ledbetter said.

“No—”

“ ‘All seated on the ground.’ Here,” he said, rewinding. “Listen.”

He played it again. I watched the Altairi, focusing on picking out the sound of the Muzak through the rest of the noise. “ ‘While shepherds watched their flocks by night,’ ” the choir sang, “ ‘all seated on the ground.’ ”

He was right. The Altairi sat down the instant the word “seated” ended. I looked at him.

“See?” he said happily. “The song said to sit down and they sat. I happened to notice it because I was singing along with the Muzak. It’s a bad habit of mine. The girls tease me about it.”

But why would the Altairi respond to the words in a Christmas carol when they hadn’t responded to anything else we’d said to them over the last nine months? “Can I borrow this videotape?” I asked. “I need to show it to the rest of the commission.”

“Sure,” he said, and asked Mrs. Carlson.

“I don’t know,” she said reluctantly. “I have tapes of every single one of Belinda’s performances.”

“She’ll make a copy and get the original back to you,” Mr. Ledbetter told her. “Isn’t that right, Meg?”

“Yes,” I said.

“Great,” he said. “You can send the tape to me, and I’ll see to it Belinda gets it. Will that work?” he asked Mrs. Carlson.

She nodded, popped the tape out, and handed it to me. “Thank you,” I said, and hurried back over to Dr. Morthman, who was still arguing with the mall manager.

“You can’t just close the entire mall,” the manager was saying. “This is the biggest profit period of the year—”

“Dr. Morthman,” I said, “I have a tape here of the Altairi sitting down. It was taken—”

“Not now,” he said. “I need you to go tell Leo to film everything the Altairi might have seen.”

“But he’s taping the Altairi,” I said. “What if they do something else?” but he wasn’t listening.

“Tell him we need a video record of everything they might have responded to, the stores, the shoppers, the Christmas decorations, everything. And then call the police department and tell them to cordon off the parking lot. Tell them no one’s to leave.”

“Cordon off—!” the mall manager said. “You can’t hold all these people here!”

“All these people need to be moved out of this end of the mall and into an area where they can be questioned,” Dr. Morthman said.

“Questioned?” the mall manager, almost apoplectic, said.

“Yes, one of them may have seen what triggered their action—”

“Someone did,” I said. “I was just talking to—”

He wasn’t listening. “We’ll need names, contact information, and depositions from all of them,” he said to the mall manager. “And they’ll need to be tested for infectious diseases. The Altairi may be sitting down because they don’t feel well.”

“Dr. Morthman, they aren’t sick,” I said. “They—”

“Not now,” he said. “Did you tell Leo?”

I gave up. “I’ll do it now,” I said, and went over to where Leo was filming the Altairi and told him what Dr. Morthman wanted him to do.

“What if the Altairi do something?” he said, looking at them sitting there glaring. He sighed. “I suppose he’s right. They don’t look like they’re going to move anytime soon.” He swung his camera around and started filming the Victoria’s Secret window. “How long do you think we’ll be stuck here?”

I told him what Dr. Morthman had said.

“Jeez, he’s going to question all these people?” he said, moving to the Williams-Sonoma window. “I had somewhere to go tonight.”

All these people have somewhere to go tonight, I thought, looking at the crowd—mothers with babies in strollers, little kids, elderly couples, teenagers. Including fifty middle-school girls who were supposed to be at another performance an hour from now. And it wasn’t the choir director’s fault Dr. Morthman wouldn’t listen.

“We’ll need a room large enough to hold everyone,” Dr. Morthman was saying, “and adjoining rooms for interrogating them,” and the mall manager was shouting, “This is a mall, not Guantanamo!”

I backed carefully away from Dr. Morthman and the mall manager and then worked my way through the crowd to where the choir director was standing, surrounded by his students. “But, Mr. Ledbetter,” one of them was saying, “we’d come right back, and the pretzel place is right over there.”

“Mr. Ledbetter, could I speak to you for a moment?” I said.

“Sure. Shoo,” he said to the girls.

“But, Mr. Ledbetter—”

He ignored them. “What did the commission think of the Christmas carol theory?” he asked me.

“I haven’t had a chance to ask them. Listen, in another five minutes they’re going to lock down this entire mall.”

“But I—”

“I know, you’ve got another performance and if you’re going to leave, do it right now. I’d go that way,” I said, pointing to the east door.

“Thank you,” he said earnestly, “but won’t you get into trouble—?”

“If I need your choir’s depositions, I’ll call you,” I said. “What’s your number?”

“Belinda, give me a pen and something to write on,” he said. She handed him a pen and began rummaging in her backpack.

“Never mind,” he said, “there isn’t time.” He grabbed my hand and wrote the number on my palm.

“You said we aren’t allowed to write on ourselves,” Belinda said.

“You’re not,” he said. “I really appreciate this, Meg.”

“Go,” I said, looking anxiously over at Dr. Morthman. If they didn’t go in the next thirty seconds, they’d never make it, and there was no way he could round up fifty middle-school girls in that short a time. Or even make himself heard…

“Ladies,” he said, and raised his hands as if he were going to direct a choir. “Line up.” And to my astonishment, they instantly obeyed him, forming themselves silently into a line and walking quickly toward the east door with no giggling, no “Mr. Ledbetter—?” My opinion of him went up sharply.

I pushed quickly back through the crowd to where Dr. Morthman and the mall manager were still arguing. Leo had moved farther down the mall to film the Verizon Wireless store, away from the east door. Good. I rejoined Dr. Morthman, moving to his right side so if he turned to look at me, he couldn’t see the door.

“But what about bathrooms?” the manager was yelling. “The mall doesn’t have nearly enough bathrooms for all these people.”

The choir was nearly out the door. I watched till the last one disappeared, followed by Mr. Ledbetter.

“We’ll get in portable toilets. Miss Yates, arrange for porta-potties to be brought in,” Dr. Morthman said, turning to me, and it was obvious he had no idea I’d ever been gone. “And get Homeland Security on the phone.”

“Homeland Security!” the manager wailed. “Do you know what it’ll do to business when the media gets hold—” He stopped and looked over at the crowd around the Altairi.

There was a collective gasp from them and then a hush. Someone must have turned the Muzak off at some point because there was no sound at all in the mall. “What—? Let me through,” Dr. Morthman said, breaking the silence. He pushed his way through the circle of shoppers to see what was happening.

I followed in his wake. The Altairi were slowly standing up, a motion somewhat like a string being pulled taut.

“Thank goodness,” the mall manager said, sounding infinitely relieved. “Now that that’s over, I assume I can reopen the mall.”

Dr. Morthman shook his head. “This may be the prelude to another action, or the response to a second stimulus. Leo, I want to see the video of what was happening right before they began to stand up.”

“I didn’t get it,” Leo said.

“Didn’t get it?”

“You told me to tape the stuff in the mall,” he said, but Dr. Morthma

n wasn’t listening. He was watching the Altairi, who had turned around and were slowly glide-waddling back toward the east door.

“Go after them,” he ordered Leo. “Don’t let them out of your sight, and get it on tape this time.” He turned to me. “You stay here and see if the mall has surveillance tapes. And get all these people’s names and contact information in case we need to question them.”

“Before you go, you need to know—”

“Not now. The Altairi are leaving. And there’s no telling where they’ll go next,” he said, and took off after them. “See if anyone caught the incident on a video camera.”

As it turned out, the Altairi went only as far as the van we’d brought them to the mall in, where they waited, glaring, to be transported back to DU. When I got back, they were in the main lab with Dr. Wakamura. I’d been at the mall nearly four hours, taking down names and phone numbers from Christmas shoppers who said things like, “I’ve been here six hours with two toddlers. Six hours!” and “I’ll have you know I missed my grandson’s Christmas concert.” I was glad I’d helped Mr. Ledbetter and his seventh-grade girls sneak out. They’d never have made it to the other mall in time.

When I was finished taking names and abuse, I went to ask the mall manager about surveillance tapes, expecting more abuse, but he was so glad to have his mall open again, he turned them over immediately. “Do these tapes have audio?” I asked him, and when he said no, “You wouldn’t also have a tape of the Christmas music you play, would you?”

I was almost certain he wouldn’t—Muzak is usually piped in—but to my surprise he said yes and handed over a CD. I stuck it and the tapes in my bag, drove back to DU, and went to the main lab to find Dr. Morthman. I found Dr. Wakamura instead, squirting assorted food court smells—corn dog, popcorn, sushi—at the Altairi to see if any of them made them sit down. “I’m convinced they were responding to one of the mall’s aromas,” he said.

“Actually, I think they may have—”

“It’s just a question of finding the right one,” he said, squirting pizza at them. They glared.

Passage

Passage Bellwether

Bellwether Blackout

Blackout Doomsday Book

Doomsday Book A Lot Like Christmas: Stories

A Lot Like Christmas: Stories Water Witch

Water Witch To Say Nothing of the Dog

To Say Nothing of the Dog Fire Watch

Fire Watch The Winds of Marble Arch and Other Stories

The Winds of Marble Arch and Other Stories Uncharted Territory

Uncharted Territory All Clear

All Clear Crosstalk

Crosstalk Lincoln's Dreams

Lincoln's Dreams Miracle and Other Christmas Stories

Miracle and Other Christmas Stories Time is the Fire

Time is the Fire Blackout ac-1

Blackout ac-1 Dooms Day Book

Dooms Day Book Jack

Jack The Doomsday Book

The Doomsday Book Terra Incognita

Terra Incognita The Best of Connie Willis

The Best of Connie Willis Cibola

Cibola Schwarzschild Radius

Schwarzschild Radius Even the Queen

Even the Queen The Last of the Winnebagos

The Last of the Winnebagos Spice Pogrom

Spice Pogrom Oxford Time Travel 1 - Blackout

Oxford Time Travel 1 - Blackout At The Rialto

At The Rialto A Lot Like Christmas

A Lot Like Christmas